The IRA attack on Fenit coastguard station and RIC barracks in June 1920.

BY DAIRE BRUNICARDI

In most of the many accounts and histories of the Irish War of Independence very little, if any, mention is made of the navy. The navy, the ‘silent service’, then, as now, was ‘out of sight, out of mind’, but it was there, as always, underpinning the activities of the military and the civil authority. Its role may have been appreciated by some members of the Dáil and the IRA leadership but there was little they could do about it. Even in one of the actions carried out directly against the navy—a raid on a large naval motor launch in November 1919 in Bantry—the aim was to obtain weapons; it didn’t seem to cross the raiders’ minds to destroy the vessel as an enemy military asset. Had it been an RIC barracks or a military post it would almost certainly have been set on fire.

Coastguard vulnerable

The vulnerability of the coastguard and other isolated installations around the coast was of concern to the Admiralty as the revolutionary activities escalated (the coastguard then was a branch of the Admiralty and formed a Naval Reserve). By 1919 Ireland had the most complete coverage of the coast that it was ever to achieve; at every harbour and inlet there was a coastguard station—several hundred in all—and, as a result of the recent war, signal stations on many prominent headlands. There were also several Admiralty radio stations at various positions around the coast. Added to this was the manned lighthouse and light-ship service. Never again was Ireland to have such a preponderance of eyes and ears reporting to government on matters of security and maritime activity. In the opinion of the Admiralty, all of these were vulnerable to attack, as were the commercial radio stations and the submarine telegraph cable stations.

In early 1918, when it had seemed possible that there might be another rebellion in Ireland, the Admiralty reported to cabinet that, unlike the army, the navy in Ireland was in ‘the war zone’. Its bases and installations were actively engaged in fighting the anti-submarine campaign and therefore any interference with them interfered with the prosecution of the war. Therefore, in the case of serious disturbances or rebellion, the military would be required to protect these installations. The war ended without the Admiralty’s fears being realised, but they were to materialise soon afterwards.

Source of small arms

The remote and isolated situations of many of the stations made them difficult to protect, and the fact that each coastguard station held a few small arms made them an attractive target for the insurgents. The Admiralty called on the military to provide protection, as they considered this to be their function. The military, however, stated that they were fully committed to protecting their own resources and providing support to the constabulary, and that they were in no position to provide the required protection for the many remote coastguard stations. The Admiralty brought in naval marines to protect the naval radio and signal stations but they were too few to reinforce most of the coastguard.

There were many attacks on coastguard stations. In some cases the men of the coastguard put up a spirited defence, occasionally repelling the attacks. More often than not, however, they were forced to surrender in the face of overwhelming numbers. The usual number of coastguards in a station was four or five, and they were further hampered by the presence of their families. There were reports of the attackers being gallant and considerate, allowing the men to care for the safety of their families and to remove personal belongings, and even apologising for upsetting the women and children. An example of such an attack occurred at Ballyheigue on 26 May 1920, at 2am. The station was surrounded, the occupants—four coastguards and their families—were forced to evacuate, the arms were taken and the buildings were set on fire.

HMS Urchin

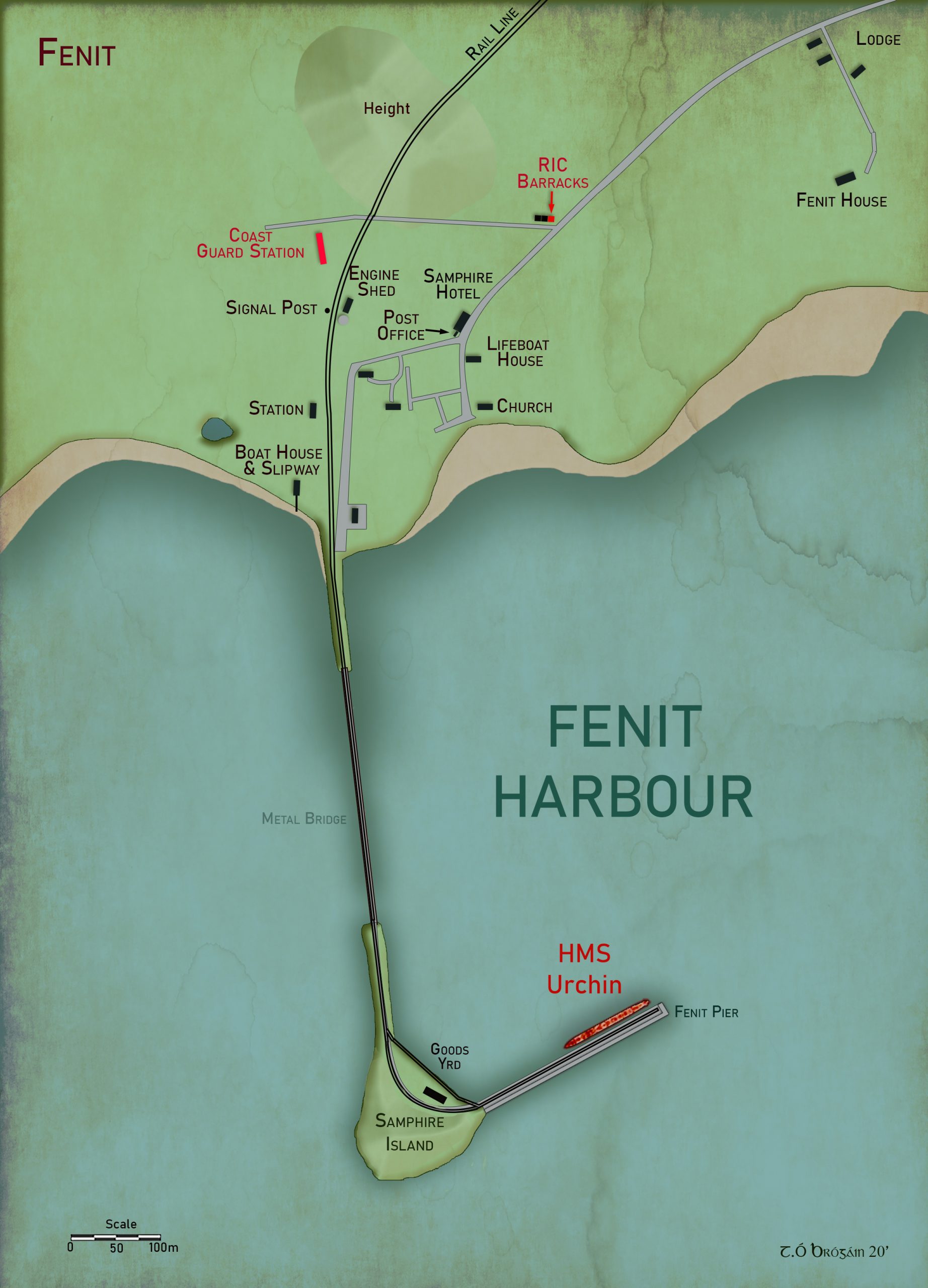

In Fenit the defence of the coastguard station was directly aided by the presence of the navy. The destroyer HMS Urchin was frequently tied up at the pier there at the end of May 1920. Her commanding officer had set up the defence of the coastguard station by sending a leading seaman and fours ABs (able-bodied seamen) each night to help defend it. These were each armed with a revolver, as well as two Lewis light machine-guns, two rifles for sentries posted outside the building, and rocket flares to raise the alarm in case of attack. The building was put in a state of defence with its windows sandbagged. These actions were further supported from the ship. The ship’s searchlight was used throughout the night to illuminate the area. An armed sentry was posted on the ship’s fo’cs’le to challenge anyone approaching and to raise the alarm if the rocket was fired from the coastguard station. Another armed party, consisting of a petty officer and four men, was detailed and ready to land if the alarm was raised, and a boat was ready to land on the beach opposite the ship if required. The forward 4in. gun was loaded with blank ammunition but the after one had live shell loaded, and both were trained towards the coastguard station.

In Fenit the defence of the coastguard station was directly aided by the presence of the navy. The destroyer HMS Urchin was frequently tied up at the pier there at the end of May 1920. Her commanding officer had set up the defence of the coastguard station by sending a leading seaman and fours ABs (able-bodied seamen) each night to help defend it. These were each armed with a revolver, as well as two Lewis light machine-guns, two rifles for sentries posted outside the building, and rocket flares to raise the alarm in case of attack. The building was put in a state of defence with its windows sandbagged. These actions were further supported from the ship. The ship’s searchlight was used throughout the night to illuminate the area. An armed sentry was posted on the ship’s fo’cs’le to challenge anyone approaching and to raise the alarm if the rocket was fired from the coastguard station. Another armed party, consisting of a petty officer and four men, was detailed and ready to land if the alarm was raised, and a boat was ready to land on the beach opposite the ship if required. The forward 4in. gun was loaded with blank ammunition but the after one had live shell loaded, and both were trained towards the coastguard station.

Rocket fired to raise the alarm

On the night of 1/2 June 1920, drizzling rain reduced visibility and made the searchlight ineffective (the reflection off the drizzle would blind the observers). At 03:00 a rocket was fired from ashore and the sentry raised the alarm. A lot of firing and some explosions were heard, but because of the thick weather little could be seen from the ship. The landing party was sent off along the long causeway connecting the pier to the shore, and a round of 4in. blank was fired. Several more rounds of blank were fired during the engagement, Lt. Commander Hughes deciding not to fire live rounds owing to the poor visibility.

It appeared that the main focus of the attack was the RIC barracks, about 500 yards from the coastguard station. A second landing party was dispatched, consisting of an officer, a signalman and some men armed with rifles and a Lewis gun. As the first party ran along the causeway, the shore end burst into flames. A party of the attackers had been detailed to destroy the causeway to prevent aid from the ship, but the quick arrival of the landing party foiled this. Fire was exchanged, but this party of attackers withdrew in good order along the foreshore. The house adjoining the police barracks was in flames and the police were firing in all directions, so it was extremely dangerous for the naval parties to attempt to approach it. The sub-lieutenant in charge of the combined landing parties made some attempt to engage the attackers, but they were well spread out under good cover and so he withdrew to the defence of the coastguard station. Lt. Commander Hughes stated in his report that the attackers seemed to be well organised and controlled by a series of whistles. Shouted orders could also be heard by the naval party but could not be understood. After about an hour, two distinct loud whistles were heard and the attack suddenly ceased. The policemen were persuaded to reluctantly come out; the sergeant was badly wounded and two others slightly.

Hughes sent a man in plain clothes on a bicycle to attempt to get to Tralee, several miles away, to alert the military and to get a doctor, as all telegraph and telephone lines had been cut. He overtook a large party engaged in blocking the road and was sent back three times. Hughes had attempted to raise the military by radio, but apparently the army shut down their radio watch at midnight.

This assault on Fenit RIC barracks was carried out by a large combined group of the North Kerry IRA under the command of Patrick Paul Fitzgerald. The barracks was a fairly new building and the attackers had the benefit of the builder in their ranks. Initially a mine was exploded at the gable end of the building, and then, having evacuated the family in the adjoining house, the attackers broke through the roof of the barracks, poured in petrol and paraffin and set fire to the building. There were eight or nine policemen in the station and two ‘Tans’. They had been called on to surrender but had refused and put up a sustained defence in the burning building.

The movements of the British destroyer over the previous weeks had been studied, along with its routines of patrols. The raid had been planned when it was expected that the ship would be absent from Fenit. Nevertheless, in spite of the unexpected presence of the ship it was decided to proceed with the attack. A party of attackers was detailed to defend the shore end of the pier, and a large quantity of straw, soaked in petrol and paraffin, was placed on the wooden structure of the pier to destroy it and prevent reinforcements arriving from the ship.

According to some accounts by participants recorded many years later in the Bureau of Military History, the fire and an exchange of gunfire repelled the landing party from the ship. Other accounts in the same source describe the fire dying out ineffectively. That source makes little mention of the coastguard station, other than to say that the regular occupants had been reinforced by a detachment of marines (probably the sailors sent from the ship). Some accounts describe shells from the ship landing in the field behind the barracks.

After the Treaty the navy was heavily involved in evacuating the coastguard stations; later, during the Civil War, it provided limited assistance to Provisional Government forces, but that’s a story for another day.

Daire Brunicardi is a former Senior Lecturer in the National Maritime College of Ireland.

FURTHER READING

D.N. Brunicardi, Haulbowline, the naval base and ships of Cork Harbour (Dublin, 2012).

J. Herlihy, The Royal Irish Constabulary (Dublin, 2016).

J.J. Lee (ed.), Kerry’s fighting story 1916–21, told by the men who made it (Cork, 2006).