By Karel Kiely

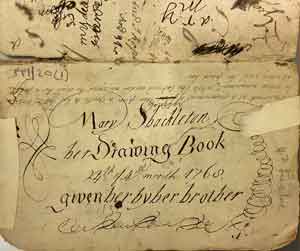

Local authority archives consist of the records of local government, including those of the various bodies which existed prior to the establishment of the present county councils in 1899. Other material, however, may be acquired or deposited, including estate, business and private papers. One such collection relating to the families of Shackleton, Leadbeater and Barrington is held in the Kildare County Archives. It includes extensive correspondence between Mary Leadbeater (née Shackleton, 1758–1826), an inveterate letter-writer, and friends and relatives, including Arabella Forbes, Amy and Elizabeth Grubb, Susannah and Mary Bewley, and Bishop O’Beirne of Meath and his wife Jane, comprising nearly 400 letters in total; there are also notebooks, diaries, an account book, sketches and poems.

The Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) has left a unique imprint on County Kildare, evident in the buildings in the village of Ballitore and the published writings of one of its most famous members, Mary Leadbeater, in which she chronicled her life in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The first recorded Society of Friends meeting in Ireland took place in 1654 at the home of William Edmundson, Lurgan, Co. Armagh. The Quakers believed in the egalitarian treatment of men and women, non-violence, a single standard of truth-telling and the setting aside of traditional customs of worship. English Quakers, Abel Strettel and John Barcroft, purchased land beside the Griese River at Ballitore in 1685, and over the next two centuries members of the Society settled what became known as the ‘Quaker’ village.

Mary’s grandfather (and great-great-great-grandfather of polar explorer Ernest Shackleton, born in Kilkea, Co. Kildare), Abraham Shackleton (1696–1771), was born in Harden in Yorkshire, taught in a school in Skipton and later came to Ireland as a tutor for two Quaker families, the Coopers and the Ducketts of County Carlow. Encouraged to open a boarding-school in Ballitore, which had a sizeable population of Quakers, he became the first master of the non-denominational school when it opened on 1 March 1726. It was a great success. Notable pupils included United Irishman James Napper Tandy, Cardinal Paul Cullen, Henry Grattan and Edmund Burke, the famous orator and political essayist. Burke maintained a correspondence and friendship with the Shackleton family throughout his life and often visited the village. Abraham’s son, Richard Shackleton (1726–92), became its headmaster in 1756.

Mary, one of four children from Richard’s second marriage to Elizabeth Carleton, was educated in the school’s classical curriculum and demonstrated an early ability for creative writing. She became skilled in herbal medicine, later ran a bonnet-making business and was the first postmistress of Ballitore village. Mary had a prodigious output of work between 1790 and 1824, the best known of which was the Annals of Ballitore. Her publications are an invaluable historical record of an Irish village, including her experience of the violence of the 1798 rebellion, when the Suffolk Fencibles burned most of the village and the body of her friend Dr Frank Johnson was thrown over a wall following his execution.

The collection of letters held in Kildare County Archives provides an insight into the daily life and intimate thoughts of Mary, her family, friends, Ballitore village and the wider Quaker community in Ireland. For example, in the letters to Amy and Elizabeth Grubb of Clonmel, Co. Tipperary (PPI/12), written between 1771 and 1818, Mary mentions her future husband, William Leadbeater: ‘I wish you would let Leadbeater’s eyes alone—they are not fit for everyone to look at—Alas! my heart aches for him’ (17 March 1781). She married William, a former pupil and French teacher at Ballitore school, in 1791: ‘that I should be gratified with so rare a thing as the union with the man of my choice, often fills me with amazement’ (19 January 1791). They had six children (five daughters and one son) between 1891 and 1801. Mary writes of the death of one daughter, ‘my little, blooming, smiling, prating Jane’, who ‘was the age, turned of four, at which I think children are most engaging, when the charm of novelty adds to the pleasure of contemplating the newly unfolded mind—she was strongly attached to me, too to me, whose stupid inattention caused her death’ (9 January 1799). Jane was severely burned when her dress caught fire from a taper she was carrying and she died a few days later.

Mary recounted the execution of two men: ‘And yesterday a new scene appeared in Ballitore, which is pretty well familiarised with horrors. A strong military guard arrested two criminals to be executed on the spot where their crimes were committed. I saw the sad procession, & the unfortunate men living and their coffins on the same car. One of them, the father of six children, they say, hung his head weeping’ (7 May 1799). She mentions correspondence sent by Colonel Keating MP, Narraghmore, Co. Kildare, concerning a bequest made by his recently deceased daughter of £500 to ‘the poor of the parish of Narraghmore’ which she wished Mrs Leadbeater to ‘be party in the arrangement of’. Mary wrote to Elizabeth that she was ‘thinking of appropriating part to the relief of the poor lying-in-women; and I want to know how much meal, tea, sugar, bread &c. you give to each, & what linen &c. is lent out’ (29 September 1811).

Many letters contain references to Mary’s literary interests: ‘the journal is much behind—to get my writing done, not to interfere with my daily business and to escape interruption, I rise an hour before day’ (24 December 1793). She says elsewhere that Maria Edgeworth has informed her that the poet Walter Scott ‘spoke in the highest manner of Cottage Dialogues [Cottage dialogues among the Irish peasantry]’ (24 October 1811).

Karel Kiely is an archivist with Kildare Library and Arts Service.