Was cricket in late nineteenth-century Ireland really an élitist activity limited to the middle and upper classes? Tom Hunt assesses the evidence for County Westmeath.

In July 1893 members of the Ringtown Cricket Club, Co. Westmeath, assembled on the shores of Lough Derravaragh to make the journey across the lake to play a match against the Stonehall Cricket Club. Thirty-two members of the club climbed on board ‘a large boat, kindly placed at their disposal by a local turf merchant’. After what was described as a delightful half-hour’s sail, ‘during which songs were sung and music rendered’, the members arrived at the Stonehall ground and dispensed with the challenge presented by the host team by an innings and seventeen runs. This image of a turf-boat full of singing and dancing young men from rural Westmeath on their way to a pre-arranged cricket game is one that is not normally associated with ‘the quintessentially English game’. It was, however, one that was very much the reality for the young men of the county, who throughout the 1880s and 1890s used whatever transport was available to facilitate participation in their chosen and favoured sport. It is also an image that illustrates the role played by cricket in bringing much-needed colour and excitement to local communities.

The role and importance of cricket in Ireland have received limited attention. There is general agreement that cricket had begun to decline in the 1880s. This has been attributed to the rapid growth of the GAA and as an indirect consequence of Land League activity. Cricket has been portrayed as an élitist activity limited to the middle and upper classes, but recent research on the game in Tipperary in the 1870s suggests that it enjoyed a more widespread popularity than is generally accepted. There is evidence that from 1870 to 1884 at least 130 different cricket clubs existed in that county.

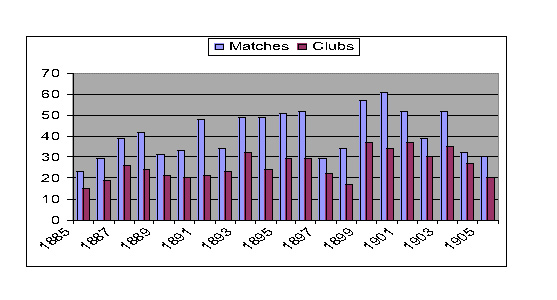

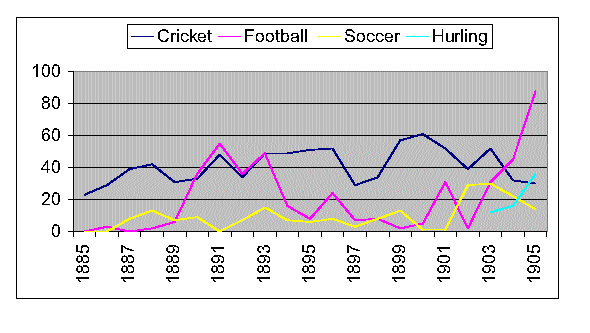

The accepted notions of cricket’s growth and decline and social exclusiveness clearly do not apply to Westmeath, where newspaper analysis reveals that cricket experienced a period of steady growth throughout the 1880s and 1890s, both geographically and demographically. In the period 1885–1905 cricket was the most popular sport in Westmeath; it was played throughout the county and attracted support from all classes. This growth peaked in 1900 when 61 cricket matches were reported in the local newspapers, played by 34 different combinations. The number of matches played and combinations active is illustrated on the opposite page.

The type of teams

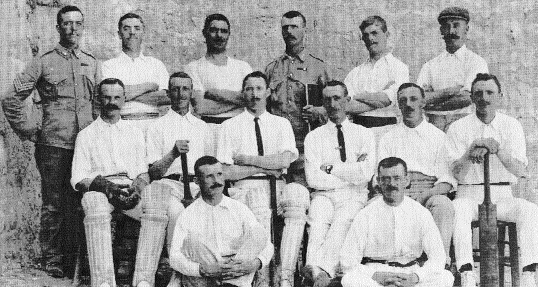

In the period 1885–1905 a total of 940 cricket matches were reported for the county, involving 173 different civilian combinations (matches involving a military team constituted 17% of games played). A number of the teams involved were transient combinations that assembled for a single match and then disbanded. Many were also properly constituted clubs that had a constitution and by-laws and held annual meetings to elect officers for the season. Regular practice sessions were organised and an annual ball was held at the conclusion of the season. Distinctive uniforms, which heightened the members’ sense of collective identity and set them apart as a community of respectable sportsmen, were also worn. The Kilbride National Club, for instance, adopted a green and white uniform for its members.

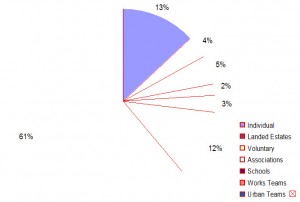

The 173 non-military cricket teams can be divided into a number of categories, and this classification highlights the broad popular appeal of the game in the 1880s and 1890s. One group, forming almost 13% of the total, consisted of well-to-do individuals who assembled a group of their friends to challenge a combination formed by individuals of similar status in the area. This group chiefly included landed estate proprietors such as Mr Clibborn and Mr F.W. Russell at Moate, Mr Murray at Mount Murray, Mullingar, and Mr P. O’Reilly of Coolamber, but also included the selection of J.H. Locke, joint proprietor of Kilbeggan distillery, and the combination of the Church of Ireland rector Revd H. St George. The élite Westmeath County Cricket Club represented the composite team of this particular group.

A second group of teams were directly associated with landed demesnes such as Lord Greville’s Clonhugh demesne, Charles B. Marley’s Rochfort establishment and in particular the Coolamber estate of the most sports-obsessed of Westmeath’s landed families, the O’Reillys. This group formed about 4% of the total. These matches formed an important part of the social life of the landed gentry and were associated with sumptuous luncheons and musical entertainment provided by the regimental bands of the Athlone- or Mullingar-based garrisons. At this level a cricket match was a good way of entertaining friends, neighbours, tenants and even labourers.

Westmeath had a number of schools that equated to the English model of the public school. In the 1890s ‘muscular Christianity’ had become part of the ethos of these educational establishments. Muscular Christianity was based on the belief that physical activity played a crucial role in developing Christian gentlemen, by teaching courage, self-reliance and character-building through the playing of sport. Participation in sport was also valued for its health-promoting virtues. According to the principal of the Ranelagh School at Athlone, Mr Bailie, there was a ‘wholesome rule’ in the school that required all boys ‘to go out two days a week and take their turns at the games, whether cricket, football or hockey’, and this involvement accounted for the excellent health of the boys. The Ranelagh School Cricket Club featured in reports for ten of the years surveyed, and the Farra School near Mullingar was also active. These schools were under the patronage and superintendence of the Incorporated Society for Promoting English Protestant Schools in Ireland.

Westmeath had a number of schools that equated to the English model of the public school. In the 1890s ‘muscular Christianity’ had become part of the ethos of these educational establishments. Muscular Christianity was based on the belief that physical activity played a crucial role in developing Christian gentlemen, by teaching courage, self-reliance and character-building through the playing of sport. Participation in sport was also valued for its health-promoting virtues. According to the principal of the Ranelagh School at Athlone, Mr Bailie, there was a ‘wholesome rule’ in the school that required all boys ‘to go out two days a week and take their turns at the games, whether cricket, football or hockey’, and this involvement accounted for the excellent health of the boys. The Ranelagh School Cricket Club featured in reports for ten of the years surveyed, and the Farra School near Mullingar was also active. These schools were under the patronage and superintendence of the Incorporated Society for Promoting English Protestant Schools in Ireland.

Voluntary associations fielded cricket teams as a means of broadening their social curriculum and extending the range of activities available to members. Included in this category are the Athlone Brass Band XI, the Father Matthew Hall XI, the teams of Castlepollard, Killucan and Mullingar Working-men’s Clubs, and the Catholic Commercial cricket clubs of Mullingar and Castlepollard. This group formed 4.6% of the total.

Another small group of teams, making up 3% of the total, may be categorised as works teams made up of employees of particular workplaces, such as the Athlone Woollen Mills, the Mullingar Mental Asylum XI and the Killucan (Railway) Station XI.

Of these clubs the Athlone Woollen Mills is worthy of particular note as the members benefited from the industrial paternalism of the proprietors, the Smith family. There were also clubs that served the sporting needs of particular employees in the urban and small town areas of the county such as Kilbeggan, Castlepollard, Moate, Delvin, Mullingar and Athlone. These clubs made up 12% of the total and had increased in number and activity by 1900. The Kilbeggan cricket club was reported to have played fourteen games in 1900, for example, and the Mount Street club in Mullingar played ten games. Finally, the largest category of teams represented the villages, parishes and townlands scattered across the county. These teams formed 62% of the total that were active between 1885 and 1905. While some of these were certainly associated with landed estates, their number and range is far too great for them to be considered as gentry-organised and supported teams. The classification of combinations is illustrated in the top pie chart.

Socio-economic profile

Data on the popularity of cricket among the various socio-economic groups of Westmeath society are presented in the bottom pie chart. The information contained in this chart was compiled from a study of a sample of 170 players drawn from seventeen different teams that played the game in 1900 and 1901. The enumerators’ forms for the 1901 census were used to profile the players. The evidence suggests that Westmeath cricket players came from a wide range of backgrounds, and from most sections of society.

Data on the popularity of cricket among the various socio-economic groups of Westmeath society are presented in the bottom pie chart. The information contained in this chart was compiled from a study of a sample of 170 players drawn from seventeen different teams that played the game in 1900 and 1901. The enumerators’ forms for the 1901 census were used to profile the players. The evidence suggests that Westmeath cricket players came from a wide range of backgrounds, and from most sections of society.

The game enjoyed its greatest popularity amongst the farm labourer and general labourer classes.

Of those identified, 41% were either general or farm labourers. Playing cricket offered members of this group the chance to earn respectability, display skill and win prestige in their own locality. Participation provided channels for gaining personal recognition and opportunities to improve status. Persons were accorded criticism or applause, respect or disapproval, as a consequence of their success or failure in their recreational roles.

The logistics of participation also made cricket attractive. Cricket was a game that required minimal equipment and was played in an injury-risk-free environment. A newspaper advertisement of 1904 gives an idea of how clubs equipped themselves. A dispute between the members of the Mornington club forced the officers to advertise the sale of its equipment: two new playing bats, two practice bats, a set of wickets and balls, a set of shin-guards and a new cricket book. This communal ownership of the basic playing gear reduced the cost of participation for individual members and made the game affordable.

The social scene

The opportunities for socialising associated with the game were also an important part of its attraction, including the opportunity to consume copious amounts of alcohol. This was an aspect of the game that came to the attention of ‘Short Slip’, who corresponded with the editor of the Westmeath Guardian in June 1888 on its importance and the necessity for its continuance:

‘It has hitherto been the custom with country clubs to provide luncheon and a half-barrel of porter for the visitors; which has entailed expense to such a degree, as to deter clubs from engaging in more than a few matches during the season. Now as a good many matches is what most players desire, I would suggest that the luncheon be left out, and a half-barrel of porter alone be supplied; each player providing his luncheon; which would be equally as satisfactory and a great deal cheaper than the other way.’

The game, at the popular level, also included more formally organised social occasions. End-of-season quadrille parties and balls were features of the social curriculum of formally organised clubs. The cricket clubs of Cloughan, Killucan Railwaymen, Turin, Ringtown and Wardenstown feature in newspaper reports describing their end-of-season balls, which were held at a selection of venues ranging from private residences to the ‘tastefully arranged barn of Clonhugh’ demesne provided by Lord Greville.

Farmers and their sons provided the second most important core support group for the game. They made up 19% of the players identified in the survey. It was this group, rather than members of the landed gentry, who made their land available for the playing fields. Newspaper reports contain numerous references and messages of thanks to local farmers for facilitating cricket clubs by supplying a suitable crease. Skilled labourers, a category that included all trades and craftsmen, with a 14% involvement, were slightly more important as participants than the shop assistant and clerk category that formed 12% of the total.

Young, single and Catholic

The men who played the game were essentially young, single and Catholic. In 1901, 23% of the group were less than 20 years of age; 37% were aged between 20 and 24; 18% between 25 and 29; and 22% were 30 and over. Players were overwhelmingly single; only 12% of the sample group were married in 1901. At the end of the nineteenth century, at this class level, sport was the preserve of the single man. Marriage brought new responsibilities, commitments and expenses, and the amount of disposable income available for investment in social and recreational activities dwindled.

In the period covered by this study cricket provided working people with their main opportunity to participate in a sporting activity. Of the years between 1885 and 1900, only in 1891 and 1892 did the number of Gaelic football games exceed the number of cricket matches. The relative popularity of Gaelic football, soccer, hurling and cricket is illustrated above.

Decline of cricket

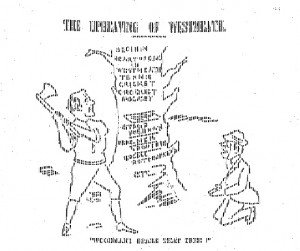

Cricket began to decline in the new century, a decline that was associated with the growth of cultural nationalism. The expansion of the GAA from 1900 onwards was part of the general revival of the broad nationalist movement that began around this time. The period 1900–5 saw the emergence of two weekly national newspapers, Arthur Griffith’s The United Irishman and D. P. Moran’s The Leader. These journals vigorously promoted cultural nationalism in its various manifestations. Cricket, soccer and other sports designated as foreign were identified as the snobbish pretensions of middle-class ‘West Britons’. In Westmeath, the Midland Reporter was in the vanguard of promoting Irish Ireland and targeting the West Briton. The concept of the cricket-playing West Briton was heavily promoted, and the newspaper specialised in the baiting and taunting of cricket-playing Westmeath men. Cricket players and playing districts were deliberately targeted and tainted with the brush of anti-Irishness.

Cricket began to decline in the new century, a decline that was associated with the growth of cultural nationalism. The expansion of the GAA from 1900 onwards was part of the general revival of the broad nationalist movement that began around this time. The period 1900–5 saw the emergence of two weekly national newspapers, Arthur Griffith’s The United Irishman and D. P. Moran’s The Leader. These journals vigorously promoted cultural nationalism in its various manifestations. Cricket, soccer and other sports designated as foreign were identified as the snobbish pretensions of middle-class ‘West Britons’. In Westmeath, the Midland Reporter was in the vanguard of promoting Irish Ireland and targeting the West Briton. The concept of the cricket-playing West Briton was heavily promoted, and the newspaper specialised in the baiting and taunting of cricket-playing Westmeath men. Cricket players and playing districts were deliberately targeted and tainted with the brush of anti-Irishness.

Another tactic adopted was to ridicule the standard of play that was found ‘in the few benighted districts in the country where alleged cricket clubs’ existed. In these cricket clubs, according to the Herald, not one of them knew how to play the game properly.

One single cricketer from England would beat the massed teams of the county, and would have by long odds, a higher score to their credit, than the whole crowd . . . Poor creatures, they are more to be pitied than blamed. They are incapable of thinking for themselves, and like a moth round a candle, they hanker after English ideas, although their limited intelligence does not permit them to imitate.’

The decline in the popularity of cricket began in Westmeath in 1903. Cultural nationalism became increasingly significant and was manifested in a number of ways. Branches of the Gaelic League were established in a number of areas; this organisation was particularly significant in the north-east of the county, where one of its officers, Peter Nea, actively promoted hurling. The organisation of Aereidheachta became a feature of the cultural life of Westmeath throughout the summers of 1904 and 1905. These events were normally promoted by the Gaelic League and featured programmes of what were considered to be native Irish song, dance, music and recitation.

The GAA was reorganised and a strong constitutional framework put in place. GAA games were now played in the summer months. The number of GAA clubs increased and provided an alternative games outlet.

Cricket bats replaced by hurleys

Hurling in particular, which was introduced to the county in 1901, specifically challenged the dominance of cricket in certain areas. Some cricket clubs provided the social network and organisational structure for newly emerging hurling clubs. The Ringtown club, for example, was one of the most stable cricket clubs in the county; it held annual meetings and regular practice sessions, and organised a regular programme of summer games and an annual end-of-season ball. After 1903 it was reconstituted as a hurling club, and became one of the leading clubs in the county. The Castlepollard hurling club, established in 1903, recruited many of its playing members from the town’s cricket clubs. The Delvin and Simonstown hurling clubs drew their core membership from a similar constituency. This trend was the reverse of what happened in the early years of the 1890s, when the GAA was initially established in the county and enjoyed a short period of relative popularity. At this time football was played during the winter–spring period and provided an opportunity for some cricket devotees to continue their sporting involvement into the winter months. The re-emergence of the GAA removed the men from the turf-boats, replaced their cricket bats with hurleys and provided the hurling pitch as the stage for some of the young men of rural Westmeath to express their athletic talent.

Conclusion

This article has illustrated the importance of cricket in the social and sporting lives of the young men of Westmeath in the final two decades of the nineteenth century. Far from being in a terminal state of decline by 1880, the game flourished up to the end of the century and embraced all social classes. Its eventual decline was associated with advances in cultural nationalism and the accompanying analysis of the nature of national identity.

In the absence of similar studies for other regions of Ireland it is not possible to determine how typical was the experience of Westmeath. There is no reason why the county should have been markedly different from other regions. Further analysis may identify whether the Westmeath pattern was broadly representative of the national position or whether there was a strong regional bias to cricket development. Recent research carried out in Tipperary indicates a pattern in the 1890s that was broadly similar.

Today only the Mullingar Cricket Club remains active. A century on, Westmeath sports followers have invested their hope in the fortunes of the county’s Gaelic footballers and their new manager, Paidí Ó Sé. Whether this latest representative of Irish Ireland delivers remains to be seen.

Originally from Waterford, Tom Hunt teaches history and geography at Mullingar Community College.

Acknowledgement

The author wishes to thank Patrick Bracken, Thurles, Co. Tipperary, for giving him access to his research on cricket in that county.

Further reading:

J. Sugden and A. Bairner, Sport, sectarianism and society in a divided Ireland (London, 1993).

M. Cronin, Sport and nationalism in Ireland: Gaelic games, soccer and Irish identity since 1884 (Dublin, 1999).

M. de Burca, The GAA: a history of the Gaelic Athletic Association (Dublin, 1980).