The British still seem intent on burying evidence of the grim deeds done in defence of their empire.

BY PÁDRAIG ÓG Ó RUAIRC

Four months after the signing of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement the Gardaí recovered the remains of an informer who had been executed by the IRA and secretly buried in a bog. Although the focus at the time was on the recovery of the remains of those ‘disappeared’ by the Provisional IRA in Northern Ireland, this body was recovered far from the border in the Galway Gaeltacht. The personal belongings buried with the body, including an engraved pocket watch, glasses and sticks of chalk, enabled the Gardaí to quickly identify the remains as those of Patrick Joyce, who had been missing since 15 October 1920.

Joyce, a Catholic school principal from Bearna, had written several letters to the British forces during the War of Independence, giving them accurate intelligence about the local IRA as well as spurious information that he had concocted about neighbours against whom he held personal grievances. Joyce’s disappearance by the IRA triggered a wave of reprisal disappearances by British forces throughout Galway and Mayo.

The phenomenon of what international human rights law terms ‘forced disappearances’ has been documented worldwide for decades. During the Spanish Civil War it is estimated that over 140,000 people were ‘disappeared’, and more recently in Syria there have been over 75,000 cases of forced disappearances. The number of disappearances perpetrated by the Provisional IRA was far smaller by comparison, yet they have attracted significant global media interest.

It has long been known that their republican predecessors also disappeared significant numbers of people during the Irish War of Independence, but it is far less well known that the British forces, and in particular the Royal Irish Constabulary, also disappeared a number of their victims during that conflict, torturing some of them in a brutal fashion before execution. At least seven people throughout Ireland were disappeared by the British forces during the war. Half of these killings were perpetrated by a single British unit—D Company of the RIC Auxiliary Division, based in Galway.

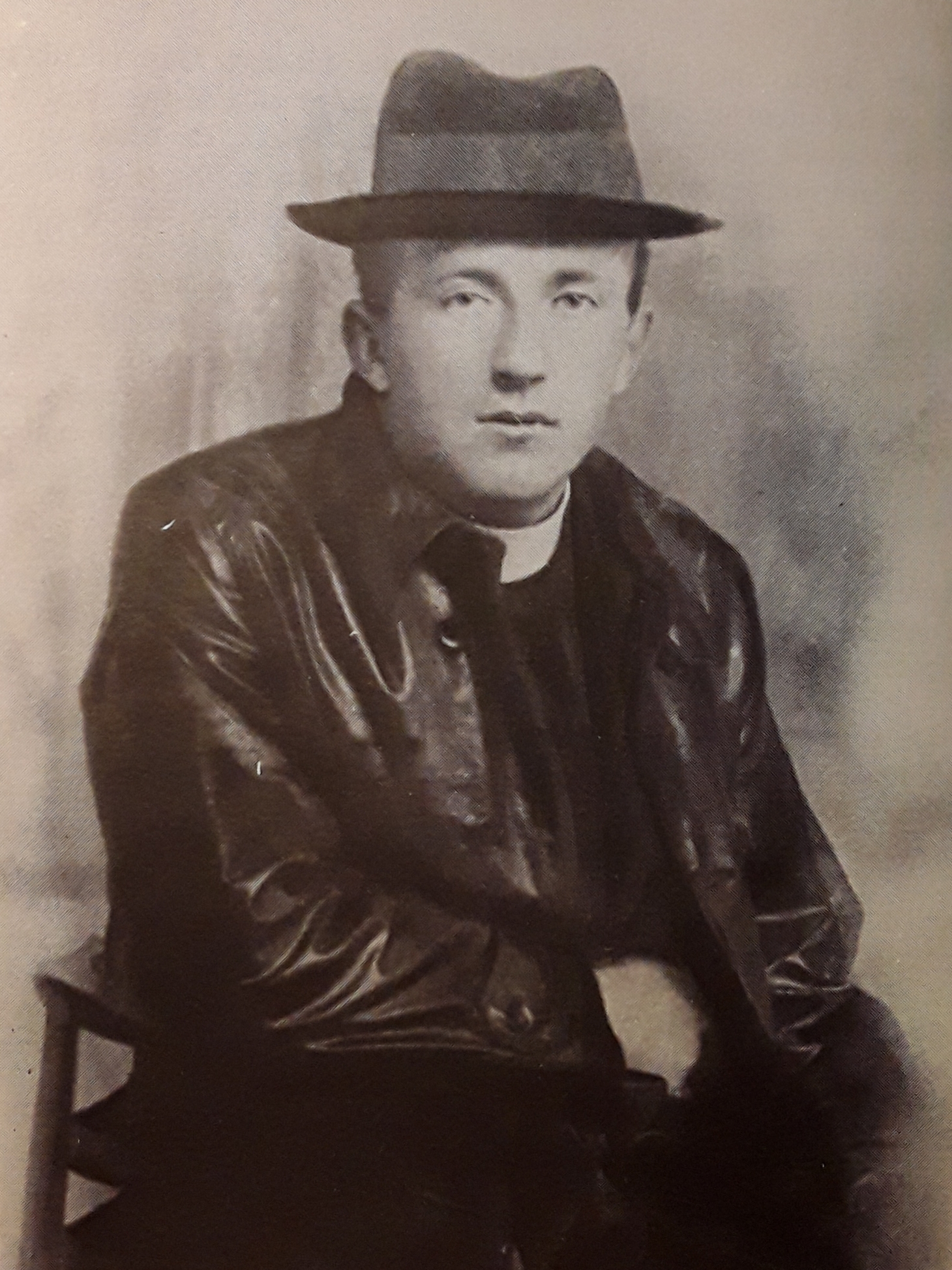

Father Michael Griffin

The first victim to be disappeared by the Auxies was Fr Michael Griffin, the curate for Rahoon, whose support for both republicanism and the Irish language revival were well known. On Sunday 14 November 1920, exactly a month after Joyce’s abduction, Fr Griffin disappeared from his home in Galway City. His body was later found in a shallow grave at Cloch Scoilte, Bearna. He had been killed execution-style with a single gunshot wound to the head.

The decision by Griffin’s killers to bury him at Bearna, the same district where Joyce disappeared, was taken deliberately to send the message that Griffin’s killing was a reprisal for Joyce. Colonel Young, a British officer who had served in Galway, made reference to it in his memoirs:

‘A loyalist wrote in giving information and by some means or other the letter was obtained for a period by the enemy … the writer was traced and killed … and a certain priest was induced to leave his house one night on a visit to the sick. Some weeks later children in the same part of the country found the partially covered body of the self same priest near a bog.’

Senior members of the British government in Ireland knew the circumstances of Griffin’s murder but were willing to indulge in any alternative explanation, no matter how fantastic, which blamed the local populace and exonerated the RIC. Mark Sturgis blamed Joyce’s relatives for the killing: ‘“Black and Tans” will of course be blamed but it is known that he and the relatives of Joyce, the schoolmaster killed by Sinn Féin in the same district, had a feud and they may have killed him in revenge’. Hamar Greenwood suggested in the House of Commons that the priest had been murdered by his own parishioners:

‘Father Griffin … and P.W. Joyce were protagonists and it is feared that Joyce had a number of friends who were determined to avenge him. Father Griffin appears to have used some strong language in the chapel on the 14th inst in which he told some of the congregation that they were as bad as the Black and Tans … I do not for a moment believe that this priest has been kidnapped by any of the forces of the Crown who are doing their best to find the whereabouts of Father Griffin.’

At the British Army court of inquiry into Fr Griffin’s killing, William Mulvagh, his next-door neighbour, stated that he saw the priest taken from his home by a group of men wearing trench coats. In an apparent case of mistaken identity, the Revd Batley, a Protestant clergyman, who was passing by at the same time, was interrogated at gunpoint by the same group. Batley testified: ‘I do not think that these were local men … these men had English accents’. The morning after the killing, Chrissie Lyons, daughter of a local RIC head constable, overheard members of the British forces joking that ‘the parson is in the bog’. Nonetheless, the British court ruled that ‘persons unknown’ had murdered Fr Griffin. The IRA’s Director of Intelligence, Michael Collins, ordered an investigation into the killing, which concluded that Fr Griffin had been held prisoner at Lenaboy Castle, headquarters of D Company of the RIC Auxiliary Division, and had been murdered by members of that unit.

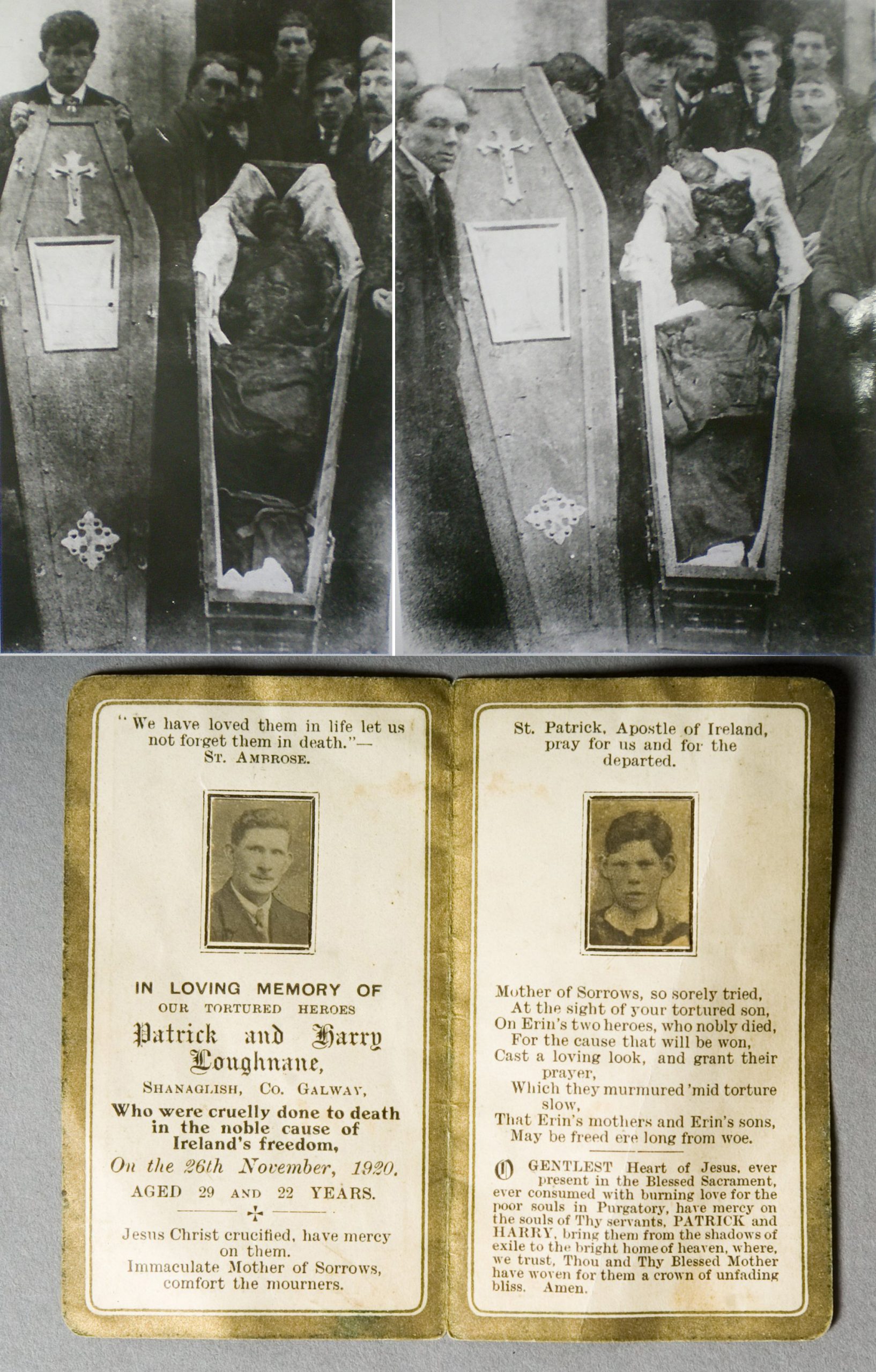

The Loughnane brothers

On 26 November 1920, members of D Company of the RIC’s Auxiliary Divison arrested two IRA Volunteers, brothers Patrick and Harry Loughnane, at their home in Shanaglish, Co. Galway. According to the British forces, the pair were then held prisoner at Drumharsna Castle. RIC Cadet V. Lawrenson stated that he was guarding the prisoners when he became distracted and they escaped from custody. He claimed that he had no opportunity to challenge them or prevent them escaping. Lt.-Col. Frederick Guard, who commanded that section of D Company, supported Lawrenson’s version of events, suggesting that the brothers, two handcuffed and unarmed prisoners, had simply vanished from inside a castle teeming with British officers who were all battle-hardened veterans of the First World War.

The battered, mutilated and charred bodies of the Loughnane brothers were discovered in an isolated pond at Ardrahan on 5 December. Dr Thomas Kennelly testified at the British military court of inquiry that ‘both bodies were charred—one was completely unrecognizable … both skulls were extensively fractured with laceration of the brain. There were no signs of gunshot wounds.’ Local republicans claimed that the brothers had been tied to the back of a Crossley tender and forced to run behind it until they collapsed from exhaustion and were dragged along the road. They further claimed that the Auxiliaries had initially attempted to bury the bodies at Ardrahan but that the land was too stony, and so they attempted to burn the bodies and destroy them with hand grenades before throwing them in the pond.

Nora Loughnane examined her brothers’ remains and gave a detailed description of their condition:

‘The bodies were hideously mutilated. They were naked save for one of Harry’s boots. There were scars and gashes, two fingers were lopped off, his right arm was broken at the shoulder and of his face nothing remained except his skin and lips. The skull was entirely blown away. The remains were badly charred. Patrick’s body was not charred to the same extent. … Mock decorations in the shape of diamonds were cut along Pat’s ribs and chest. Both his wrists were broken and his right arm above the elbow. Pat’s face was completely bashed away so as to be unrecognizable, and his skull was very much fractured.’

Nora Loughnane’s observation that the killers had cut off two of Harry’s fingers is significant. The desecration of the enemy dead by soldiers taking fingers or other body parts as grim souvenirs or ‘war trophies’ is a centuries-old practice. Troops often engage in this action when they consider their enemy to be racially inferior. Though outlawed by the Geneva Convention the practice continues, and as recently as 2011 NATO soldiers in Afghanistan were found guilty of this same war crime. The mutilation of Patrick’s body by carving diamond shapes into his torso is also noteworthy. The Loughnanes were killed by members of D Company of the RIC’s Auxiliary Division, whose unit insignia was a black and white diamond. The carving of diamonds into Patrick’s flesh by the Auxiliaries was probably intended to mark his body as a ‘trophy kill’ for the unit.

Michael Tolan

The last victim of the British forces to be disappeared in the area was Michael Tolan, a tailor and IRA officer from Ballina, Co. Mayo. Tolan was captured in his home town on 15 April 1921 and held prisoner at the local RIC barracks. His mother and sister were allowed to visit him on the following day. This was the last time that any of Tolan’s family or friends saw him alive. His family were denied subsequent visits and were later told that he was no longer being held at the barracks.

Eventually Tolan’s family hired a solicitor, P. Ruttledge, to represent them. RIC District Inspector L. Norrington wrote to Ruttledge in September 1921, stating:

‘Michael Tolan was in custody in Ballina Barracks from 15th April until 7th May. An order was granted by the Competent Military Authority for his internment, and he was handed over on the latter date to an escort of Galway police, who returned to Galway that evening. I am informed that he did not arrive at the Galway internment camp, and am communicating with the authorities there, to obtain fuller information.’

Two weeks later the RIC again wrote, stating: ‘Owing to the absence on sick leave of some of the Auxiliary Police who are concerned in the case, it has not been possible as yet to complete inquiries’. The family received no further communications from them regarding Michael Tolan’s whereabouts. Tolan was already long dead by this time. His body had been discovered in Shraheen Bog, north of Foxford, by a local man walking with his dog. The British Army subsequently held an inquest into the death of this ‘unidentified man’.

RIC Sergeant Daniel King gave evidence that the deceased had been wearing a shirt collar stamped ‘J.J. Murphy outfitter—Ballina’ and had a tailor’s thimble in his pocket. Despite the obvious evidence that the deceased was a tailor from Ballina, Sergeant King made no connection between the discovery of the body and the disappearance of Tolan, declaring that ‘all efforts to obtain identification have failed’. Tolan’s body had a bullet wound to the left side of his chest. Although the body was clothed when discovered, his genitals were missing, as was his right arm. The British inquest ruled that ‘there is not sufficient evidence to establish the cause of death’. The British authorities had Tolan reburied in an unmarked grave at League graveyard near Ballina. In October 1921 the IRA established that the unidentified body discovered at Shraheen Bog was Tolan’s. His remains were exhumed and reburied with full military honours in the Republican Plot at Ballina.

Conclusion

No members of the RIC Auxiliary Division were ever charged or prosecuted for the killings of Tolan, the Loughnane brothers or Fr Griffin. Nor was anyone prosecuted for the killings of any of the other victims who were disappeared by British forces by burying them in secret or dumping them in rivers. These include John Connolly, an IRA officer from Bandon, who was abducted and killed by British soldiers from the Essex Regiment and buried in a shallow grave at Lord Bandon’s demense. Thomas Hodgett, a Protestant postmaster from Navan, was shot dead by members of the regular RIC, who dumped his body in the Blackwater in a failed attempt to conceal evidence of their crime. Likewise, Nicholas Prendergast, an ex-British officer and Home Ruler, was abducted by members of the RIC Auxiliary Division and drowned in the Blackwater. These killings and others perpetrated by the RIC conflict with the recent statement by Minister for Justice Charlie Flanagan that members of the RIC killed during the War of Independence were just ‘doing their job … they were protecting communities from harm … they were maintaining the rule of law’.

Study of the Irish revolution is crucial to an understanding of the history of both Britain and Ireland in the twentieth century. Throughout the ‘decade of centenaries’, people in Ireland have been breaking taboos in analysing the history of the Irish revolution in minute detail. Every aspect of our history, no matter how painful, is now open for discussion in Ireland—from the killing of children to sexual violence or forced disappearances. There seems, however, to be a reluctance in Britain to adopt the same approach. Despite the confidence of Liam Fox, British secretary of state for international trade, who declared in 2016 that ‘The United Kingdom is one of the few countries in Europe that does not need to bury its twentieth-century history’, others seem to be warier. The British government’s Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, which oversees official British State commemorations, ignored the advice of its advisory panel of expert historians by deciding not to extend the First World War commemorative events to include the aftermath of the conflict, including events in Ireland and India. Whilst the Irish are shining a light into the dark corners of our revolutionary past, the British still seem intent on burying evidence of the grim deeds done in defence of their empire.

Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc has a Ph.D in Irish history and has written several books on the Irish revolution, 1916–1923.

FURTHER READING

A. Bielenberg & P. Óg Ó Ruairc, ‘Shallow graves: documenting and assessing IRA disappearances during the Irish Revolution’ (forthcoming).