On the 150th anniversary of the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland in 1869.

By Kenneth Milne

‘The Church of Ireland’, the name by which the Irish province of the Anglican Communion is known, has its roots in the sixteenth-century Reformation, when the Tudor monarchs imposed on the Irish church the Reformation settlement already brought into being in England. Henceforth, the reformed ‘Church of Ireland’ was the State—that is to say, the ‘established’—church. It was enshrined by this name in the 1937 Constitution of Ireland, Bunreacht na hÉireann, with the names of other Irish churches until, in 1972, these titles were deleted from the Constitution by referendum, together with the ‘special position’ (whatever that meant) of the Holy Catholic Apostolic and Roman Church.

The Tudors deemed the reformed church a Protestant one, and to this day for many people in Ireland the words ‘Protestant’ and ‘Church of Ireland’ are synonymous—to the understandable indignation of members of other Protestant churches, who may regard themselves as holding more closely to Reformation principles. For several generations Anglicans (as we would call them now) were the ‘original’ Protestants until joined in large numbers, mainly through the Ulster Plantation, by Protestants of another Reformation tradition, on whom, be it said, they looked with, if anything, less favour than on those who remained loyal to Rome.

Continuity with the pre-Reformation church

While the established church was unequivocally Protestant, it nurtured, and continues to do so, with its bishops, set liturgy and such institutions as cathedral chapters, continuity with the pre-Reformation church. The Book of Common Prayer (2004) includes ‘A list of persons associated with dioceses of the Church of Ireland’ that includes Patrick, Brigid and Columba, but also Edan of Ferns and Killan of Kilmore, and there are numerous church and cathedral dedications that mention saints (frequently little known) of the early Irish church. The annual Church of Ireland Directory, which lists dioceses, parishes and clergy, also includes the Irish-language derivations of many parishes, with translations. When early in the present century books were published tracing the story, past and present, of the laity and clergy of the Church of Ireland, in both cases the time-span covered was the years 1000–2000.

Being the State church did, of course, mean that the State had a significant—indeed, controlling—role in its life. The appointment of archbishops, bishops and other dignitaries was in the hands of the State, and church property was at the disposal of the State (as the established church found to its cost from the mid-nineteenth century onwards). Such constraints, however, were considered a price worth paying in return for the privileges that went with established status. The Irish archbishops and bishops were represented in the House of Lords at Westminster, and the church benefited, in one form or another, from the payment of tithes. When the National Schools were introduced in 1831, some Church of Ireland bishops, believing that the prerogatives of the established church entitled it to a more prominent place than it was given in the system, were so indignant that they created a parallel system of elementary education—the Church Education Society.

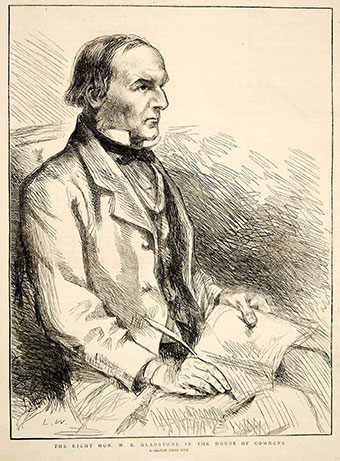

It was always likely, perhaps inevitable, that the privileges accorded the established Church of Ireland would be seriously called into question by governments as the democratisation of the United Kingdom gained pace in the late nineteenth century. It was generally recognised that the church commanded the loyalty of only a minority of the population of the island (how small a minority would be revealed by census returns from mid-century onwards). The church, however, had always stressed that its role was vital to the maintenance of the political relationship with Great Britain as a component of a United Kingdom since 1801. The Act of Union combined not only the two kingdoms of England and Ireland but also the two established churches into one United Church of England and Ireland ‘for ever’, to quote the act (albeit, to quote the historian J.C. Beckett, ‘an institution that had no being save in the minds of lawyers and on the title-page of the prayer book’ and ‘for ever’ proving to be only 70 years!). Yet what strengthened demand for disestablishment of the Irish provinces of Armagh and Dublin was the growing acknowledgement among English politicians that the established church in Ireland was itself part of the problem. W.E. Gladstone, leader of the Liberal Party, was convinced that this was the case.

Gladstone’s mission

The Fenian rising of 1867, though seemingly a failure, had demonstrated the growth of national feeling and Gladstone set himself the task of ‘pacifying Ireland’. Land reform was a major concern, but so, too, was the position of the established church, and in tackling that issue he had the support of a substantial proportion of the members of his Liberal party, many of whom were Protestant dissenters who identified with the Church of Ireland’s critics.

In March 1868 Gladstone, as leader of the opposition in the House of Commons, moved resolutions that summed up his policy: that the established Church of Ireland should cease to exist ‘as an establishment’. His resolutions were passed and the Conservative government, having been defeated on such a major issue, had little option but to call a general election. Astonishing as it may appear today, the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland was a main plank of the Liberal platform during the campaign that raged throughout Britain and Ireland. Gladstone won by a significant majority and without delay he set about achieving his goal.

Representative Church Body

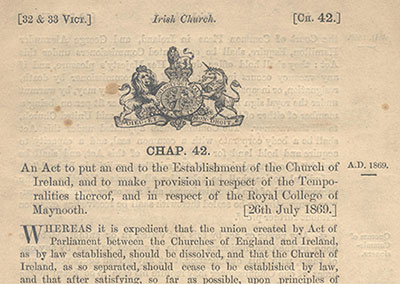

The process whereby the church was disestablished is a superb example of Victorian bureaucracy. The Irish Church Bill was very much the prime minister’s own work, drawing on somewhat similar legislation that had worked successfully in Canada. It not only disestablished the church but also largely dis-endowed it. On 26 July 1869, the day on which the Irish Church Act received, to Queen Victoria’s considerable distaste, the royal assent, the greater part of the endowments and the property (except for churches then in use, together with their churchyards) of the established church were vested in commissioners. In 1870 a Representative Church Body (RCB) was created by royal charter, and all cathedrals and churches were vested, gratis, in the RCB, with rectories and schools being available for purchase on very reasonable terms.

Gladstone had always made it clear that the interests of clergy and others who had previously received their emoluments from church endowments would be protected, and this undertaking was scrupulously adhered to. An ingenious scheme was devised whereby the financial life interest of these individuals could be compounded and the resulting funds entrusted to the RCB, from which they would receive (initially quarterly) ‘stipends’.

Gladstone acknowledged that the fledgling disestablished church would need time to set in place the necessary legislative and administrative structures for its new lease of life. Therefore the Irish Church Act stipulated that disestablishment would only come into effect on 1 January 1871, providing eighteen months in which the necessary preparation could take place. While the leaders of the church had refused to treat with Gladstone when he was piloting his bill through parliament (though, as is usually the case in such situations, there were back-channel contacts), once the die was cast the church tackled the task before it with some urgency.

The Act authorised the bishops, clergy and laity to set up a constitutional body to legislate for the church, which they duly did; a written constitution (little altered in its essentials to this day) was drafted, and synodical government instituted. After much discussion, heated at times, a way was achieved of combining governance based on principles that gave meaningful representation and powers to clergy and laity within an episcopal church. The parishes elect representatives, two lay for each of the clergy, to their diocesan synod, and the diocesan synods in turn elect to the General Synod, which is the supreme deliberative and legislative body. Although the house of bishops (which sits apart from the house of lay and clerical representatives, though in the same chamber) has what amounts to an ultimate veto, under very strict terms, on decision-making, in practice this power has never been invoked.

Gladstone knew that the dis-endowed church would require considerable lay support, in terms of both voluntary service and finance. As it happened, the period when the Church of Ireland was finding its feet administratively coincided with years in which local government in Ireland was passing from what might have had some appearance of ‘Ascendancy’ rule into nationalist hands, and so there was much administrative experience and expertise at the church’s disposal when most needed. It was noteworthy that many of the lay participants in church administration at both parish and diocesan levels had held rank in the armed services. Likewise, the lay response was ready and generous when the RCB appealed to the laity to augment the finances of the church.

Other churches affected

With the withdrawal of State funding from the Church of Ireland came the cessation of financial support for other churches. The annual grant to the Royal College of St Patrick at Maynooth and the regium donum towards the maintenance of the Presbyterian ministry were replaced by once-off grants. Another sum was put into the public domain through funding for Intermediate Education, an area of public interest in which the State (already heavily involved in elementary education) was taking an increasing interest.

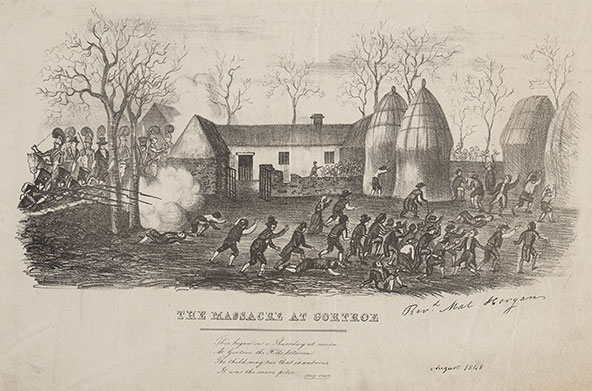

Gladstone perceived, accurately, that the established position of the Church of Ireland was a nationalist grievance, as well as being an affront to other churches. Yet that sense of grievance has not lingered in folk memory to anything like the same extent as the Tithe War, the Land War or the Great Hunger—largely because the Irish Church Act removed its cause. Therefore the significance of that statute can surely claim the interest of a much wider public than the members of that particular church, who have long since learned to regard Gladstone as a benefactor. It is worth remembering that many of those who experienced the trauma of disestablishment lived to undergo a similar, perhaps greater, shock with the success of the independence movement, and they may well have wondered what the situation of their church would have been had Gladstone not had his way.

Though the prime minister’s opponents, and in particular the Irish episcopate, strongly disputed the fact, Gladstone had no wish to penalise the church. Nor, to be fair, were the sentiments of his critics entirely based on material considerations. Mrs C.F. Alexander, wife of the bishop of Derry and whose ‘There is a green hill far away’ and ‘Once in royal David’s city’ are renowned for their lucid expression of theological truths, is sometimes chided for the hymn she wrote to be sung in her husband’s cathedral as disestablishment came into effect on 1 January 1871. Its line ‘Dimly dawns the New Year on a churchless nation’ appears to the modern mind dismissive of the existence of other churches and of Irish realities. Her real anguish, however, was not only at the loss of privilege, though undoubtedly that played a part, but also at what represented a secularisation of the state.

Gladstone was genuine in his assertion that he had no wish to damage the Church of Ireland. Certainly it would lose its privileged position and much of its property (making the Irish Church Act, in many respects, the first land act), but the act secured the church as a voluntary body. He always insisted that, while it was intended to make the severance from the State complete, care would be taken ‘not in any way to impair the means of action belonging to her [the disestablished church] as a Church or religious society’. This included the church’s freedom ‘to assert any and every claim she might consider herself to possess on other than statutory grounds’. This could be interpreted to mean that, though disestablished, she was still ‘the Church of Ireland’.

A great concern among some leaders of the church was that there were among its members those who would take advantage of its newfound freedom to distance it from current trends in the Church of England. Certainly, among the first tasks that the General Synod set itself was revision of the Book of Common Prayer. And undoubtedly among those pressing for revision were many who wished to emphasise more clearly the Church of Ireland’s Protestant heritage. The prayer-book authorised for use in 1878 did, following years of intense debate, depart in some measure from that of 1662, and the determination to prevent the spreading to Ireland of the ‘ritualism’ that was perceived to be influencing the Church of England is clearly evident in some of the canons ecclesiastical introduced in 1878. There is general consensus, however, that doctrinally the revised Book of Common Prayer did not, as some had feared, impair the church’s ‘Catholic’ credentials. To quote J.C. Beckett again, ‘… the very fact of self-government had made it possible for people to accept compromise with a good conscience’.

Kenneth Milne is Church of Ireland historiographer and Keeper of the Archives at Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin.

FURTHER READING

T.C. Barnard & W.G. Neely (eds), The clergy of the Church of Ireland (Dublin, 2006).

P.M. Bell, Disestablishment in Ireland and Wales (London, 1969).

M. Empey, A. Ford & M. Moffitt (eds), The Church of Ireland and its past(Dublin, 2017).

R. Gillespie & W.G. Neely (eds), The laity and the Church of Ireland: all sorts and conditions(Dublin, 2002).