Abigail Francis Woods’ Relationship with Charles Stewart Parnell, Ireland’s “Uncrowned King”

Over his seventeen year career (1874-1891), Charles Stewart Parnell achieved more influence than any Irish politician before him. He led the Irish Parliamentary Party, which sought Home Rule for Ireland, and he presided over the Irish National Land League, which battled landlords and their agents for more equitable treatment for Ireland’s tenant farmers. When he was at the height of his power in the 1880s, Parnell controlled enough seats in the House of Commons to be able to choose the British prime minister. His career and the constitutional nationalist movement were famously upended when his long running affair with Katharine O’Shea was made public. What is less well known is that Parnell had been engaged to a young woman from Rhode Island, Abigail Francis Woods, ten years before he met Mrs. O’Shea. Had Parnell married Miss Woods, their lives and Ireland’s fate might have turned out very differently.

Parnell’s Early Years

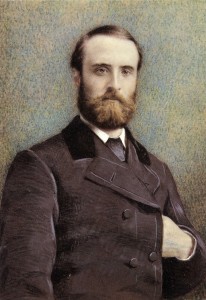

Parnell was born in 1846 at Avondale, the family estate in County Wicklow. He was the seventh of his parents’ eleven children. Parnell’s mother, Delia Stewart, was an American belle, the daughter of Commodore Charles Stewart, who had played an important role in the War of 1812. Parnell’s father, John Henry Parnell, an Anglo-Irish landlord, was the grandson of Sir John Parnell, an Irish parliamentary leader in the 1780s and ’90s. John Henry had met Delia in Washington, D.C. in 1834 when he and a cousin were traveling around America on their Grand Tour. John Henry and Delia were married a year later in an Episcopal ceremony at Grace Church in Manhattan. While Delia dutifully accompanied her husband to Avondale, she never adjusted to living in rural Ireland and spent much of her time with relatives in France and America.

When Charles was only seven, his father decided to have him educated in England. He studied briefly at two English schools before returning home to be tutored. He proved himself an indifferent student, more interested in cricket than academics. At nineteen, he entered Cambridge University, intending to study mathematics. He was not a particularly diligent student there, either. Nor was he politically engaged. In 1867 when the Fenian revolutionaries launched a rising in Dublin and other Irish cities, Parnell appears to have taken little note of it. During his fourth year, he got involved in a drunken brawl and was dismissed for the rest of the term. Parnell’s biographers contend that he could have apologized and gotten readmitted, but he chose not to do so and left Cambridge in the spring of 1869 without a degree. He returned to Avondale, which he had inherited on his father’s death in 1859, and set about improving it. He promoted logging and mining as well as farming on the 5000 acre estate.

“Almost Inseparable”: Charley and Abby

In the beginning of 1870, Charles decided to visit his mother and his bachelor uncle, Charles Stewart, who were residing in a fashionable neighborhood in Paris. At a party given in February at his uncle’s home for the city’s English and American set, Charles met Abigail Woods, whose family socialized with Stewart in Newport, Rhode Island. Abby had a distinguished pedigree: her mother, Anne Brown Francis, was a great grand-daughter of John Brown, the wealthy industrialist, politician and slave trader, who with his brothers Moses, Nicholas and Joseph dominated eighteenth century Rhode Island. Anne’s father, John Brown Francis, had served as the governor of Rhode Island in the 1830s and as a United States senator in the 1840s. Abby’s father, Marshall Woods, was trained as a medical doctor but never practiced. Instead, he served from 1867-1882 as the treasurer of Brown University, a position he held because of his links to the Brown family.

In 1855 Marshall had represented Rhode Island at the Paris Exposition and had served as a juror for the fine arts entries. He returned often to Europe in the following years to expand his art collection and sightsee. In 1870 he set sail again, bringing Abby with him on an extended European and Middle Eastern tour that would include London, Paris, Venice, Constantinople, Cairo and Jerusalem. The trip was meant to expose her to Western art and culture but also to help her find a suitable husband.

Parnell’s older brother John was at the party where the two met. He described Abby as “fair-haired, extremely beautiful and vivacious,” and declared that “Charley fell a complete slave to her attractions.” As his mother was from Boston, Charley would no doubt have been quite willing to marry an American. John admitted that Abby’s “being heiress to a large fortune” was also appealing to Charley, but was not the driving force in the relationship. John recalled that after Charley and Abby’s first meeting, they were “almost inseparable. They attended most of the principal social functions, where they were always to be seen together…Their engagement was everywhere recognized, and they were the recipients of the warmest congratulations.”

After a couple of weeks in Paris, the Woodses headed to the Middle East, stopping first in Venice. Shortly after they arrived, Charley met up with them and presented Abby with a ring. After a few happy days together, the Woodses set off for Egypt and Charley returned to Avondale. Writing to her mother from Italy, Abby declared, “I am enjoying it so much that I am glad I came for more reasons than one. I am perfectly content and only worry when I think how anxious I know you will be but I am very prudent.”

By May Marshall and Abby had returned to Paris, having seen the Sphinx and the pyramids, the Holy Land and Constantinople. At the end of the month, when Abby turned twenty-one, she wrote fretfully to her mother, “It seems scarcely possible that I am so old.” In a follow up letter, she explained her fears, “I am sure that if I do not marry soon, I shall never marry at all.”

Abby and Marshall both loved Paris. He enjoyed its art, its food and its comforts while Abby was happy to see Charley and visit Paris’ fine clothing stores and its beautiful churches. A devout Baptist, Abby faithfully attended Protestant services every Sunday. She also continued to attend formal parties at which family friends would try to introduce her to more appropriate suitors than Charley. Delphine Read, the wife of Marshall’s cousin John, urged her to consider marrying a “titled foreigner.” Marshall, too, sought to separate her from Charley. When she told him about a friend’s engagement to a wealthy American, he remarked, “Well, she can get such a man and you can’t.”

By the end of June, Abby was anxious and uncertain about how to proceed. She confided to her mother, “The more I think of it, the more worried I become. Just think of the letter that I should have to send.” She was still upset a few days later: “You cannot tell how perplexed I am about him. Be sure and answer me at length.”

In August, Abby’s gold ring broke in two pieces. She told her mother that she had had it fixed and was once again wearing it “and afterwards wrote him about it. He says he is not at all superstitious and hopes I am not.” By the end of August, the Woodses reluctantly evacuated Paris for London. The Franco-Prussian War had begun in July and the Germans were rapidly moving into France. A French partisan, Abby sadly reported France’s rout at the Battle of Sedan: “You will have heard the dreadful news of the defeat of the French Army and the Emperor [Napoleon III] being taken prisoner.”

While in London, Abby was visited by an American friend, George Bradley. He, too, was hostile to Charley: “He thinks I am engaged to _______ and he cannot bear him. I do not wonder for he treats people so coldly and contemptuously.” Bradley’s remarks rattled her further. She asked her mother, “[W]hat shall I do? What can I do to get out of this?” Abby had in fact already written Charley a letter breaking off or at least questioning their engagement and expected a reply from him in early October. She told her mother that she thought she had done “right in writing him for it will give me an opportunity of knowing how he feels about it.”

Anne, for her part, was not at all sure what advice to give Abby. Writing to Marshall in September, Anne first declared that Abby was “probably acting wisely in not deciding it fully and finally till her return home when the decision will not be thrown on you personally.” Later in the same letter, however, she indicated more openness to the marriage: “If the case is clear to her own mind to give a favorable decision, I see no sufficient reason for delaying her decision. If the case is not clear in her mind, then delay or a negative decision may be the wise course.” Three days later, Anne wrote again to Marshall. She finally concluded that “the wiser course for her to pursue is to make no decision until she sees her Mother. But after her return home, I suppose she must at an early day, decide one way or another.”

At the end of September, Abby wrote her mother from Wales and assured her that she was feeling better. She promised that she was not making herself sick and had decided to leave her dilemma “to God knowing that he will take care of it all and in his own good time show me what to do.” Two weeks later, Abby received a letter from Charley and to her surprise he made no reference to her dramatic September letter.

Before setting sail for home, Abby wrote again to Charley. This time she made a copy for her mother and her grandfather, Dr. Alva Woods. She hoped that her mother approved and assumed that her grandfather would be “very much pleased that it is all over.” Still, the letter must have had some ambiguity in it because a few days before her departure, she told her mother that she was “quite anxious to know what ____ will do about seeing me again or no. It would, I think, be wiser if he did not see me. It will only be a trial for us both.”

John Parnell recalls that Charley was at Avondale preparing his home for Abby when he received her note. John described it as a “short and not very informative letter” notifying Charley that she and her father were heading back to their home in Rhode Island. She made no reference to their engagement and did not give him any indication that she was sorry to be parting from him. John stated that his brother was “dumbfounded” by the letter and decided to discuss it with her in person.

In the spring of 1871, Charley booked passage on a ship that would arrive in New York City in early May. When he got to New York, he sent a telegram to Abby, informing her that he would be at her home in Providence that evening. When Parnell reached the Woods’ mansion, Abby greeted him warmly. John reported that Charley was initially reassured that “things were as they had been before.” After a few days, though, the situation changed suddenly once more with Abby informing him that “she did not intend to marry him, as he was only an Irish gentleman without any particular name in public.”

Leaving Rhode Island, a disheartened Parnell traveled to Alabama to visit his brother John, who had purchased a plantation there a year earlier. John recalled that Charley appeared “very sullen and dejected” but made no mention of what had happened to him. A few days later, upon prompting from John, Charley “poured forth the pitiful tale of his love for Miss Woods and how she had suddenly jilted him.” To distract him, John took him to see the neighboring farms and the cotton factories in nearby Birmingham. Over the following weeks, Charley visited much of the South from Louisiana to Virginia.

Entering the Political Fray

Charley found little that he liked in the South, which was still reeling from the ravages of the Civil War. He had no interest in settling there and eventually was able to persuade John to sell his property and return with him to Ireland. On New Year’s Day, 1872, the two set off from New York City for home. Returning to Avondale, Charley and John oversaw the workings of the farm and the saw mills. They also took note of the political changes occurring in Ireland. The Home Rule Party, founded in 1870 by Isaac Butt, a prominent Protestant attorney, was gaining momentum. Butt and his allies wanted an autonomous parliament in Dublin, much like the one in which Sir John Parnell had served in the 1780s and’90s. In 1873 John encouraged Charley to follow their great-grandfather’s example and run for a parliamentary seat. To John’s surprise, Charley told him that he had been seriously considering it for some time.

However, when the Liberal prime minister, W.E. Gladstone, called a general election at the beginning of 1874, it was Charley who prevailed upon John to run for a seat. John ran as a Home Ruler in his own district but was defeated. A month later, a special election was called to fill a vacant seat in County Dublin and this time Charley decided to make a bid for it. Although he had the strong backing of the Home Rule leaders, Parnell ran a poor campaign and was soundly beaten by his Conservative opponent.

Undeterred by his loss, Parnell continued to attend Home Rule meetings and maintained good relations with Butt. In 1875, a seat opened in County Meath and Parnell decided to contest it. This time he proved more adept at campaigning and more comfortable speaking before crowds. He called not only for Home Rule but for better treatment for Ireland’s tenant farmers and warned that the Irish might very well take up arms if the British government continued to ignore their concerns. Parnell’s defiant stance appealed to many voters and enabled him to defeat his Conservative opponent handily.

In April 1875 Parnell took his seat in the House of Commons. Although only twenty eight, he quickly assumed a leading role in the Home Rule party. He gave several speeches and, unlike some of his fellow Home Rulers, never missed a vote. He also familiarized himself with the Commons’ complex procedures and figured out how to obstruct its workings. While Butt generally frowned on obstructionism, he did not press Parnell on the subject.

In 1876, Parnell was elected a vice-president of the Home Rule Confederation of Great Britain. On July 4th, militant nationalists staged an event in Dublin commemorating America’s Centennial and invited Parnell to take part. Speakers at the event congratulated America for its hundred years of freedom from English rule but also noted that Ireland was still waiting for its freedom after seven hundred years of British control. After the rally, the organizers decided to send Parnell and another Home Rule M.P., John Power O’Connor, to America to present their Address to President U.S. Grant. Power O’Connor, who represented County Mayo, had ties to the Fenian movement.

Parnell set off two weeks early so he could see his mother, his brother John and his younger sister Fanny who were then in New York City. When Power O’Connor arrived, the two men went to Philadelphia to see the Centennial Exhibition, a grand festival showcasing everything from farm equipment to the latest inventions such as electric lamps and telephones. In New York, Parnell and Power O’Connor had the chance to meet the president and explain the reason for their trip. Grant was polite but noncommittal and encouraged them to go down to Washington, D.C. and discuss the address with his aides.

When the two reached Washington, they learned from Grant’s secretary that the address had to be submitted to the British Ambassador before it could be formally presented to the president. Considering the letter’s tone, Parnell and Power O’Connor did not expect that he would approve it. Still, they sent it off and as they anticipated, the ambassador refused to endorse the address and so Grant never ended up seeing it.

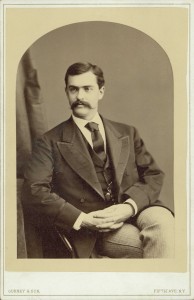

The Abbots

During his two months in America, Parnell had been in New York, Philadelphia and Washington, DC and had even ventured down to Virginia to examine a coal mine that he had invested in at one point. He did not travel to New England, though, to see Abby Woods. If he had tried to visit her, she probably would not have had the time or inclination to see him. In October 1873, Abby had married Samuel Appleton Browne Abbott, a Harvard-educated lawyer and Civil War veteran from Lowell, Massachusetts. In 1874 Abby had given birth to a daughter, Helen, and by 1875, she seemed to be overwhelmed by her responsibilities. At least that is the impression that Sam conveyed in the letters that he sent to his father, Josiah, who was then traveling through Europe. Sam frequently expressed concern that Abby was “used up” and needed to get her strength back. In June he told his father that “next Tuesday we head to Newport and I shall try to be there as much as possible for I find Abby does not get on well at all when I am away. She gets very nervous and that of course uses her up. She seems to be somewhat better now.” In the fall of 1876, Abby was about to deliver their second daughter, Madeleine, so it is hard to imagine that she would then have been up to visiting with Parnell.

Ireland’s “Uncrowned King”

Although his American mission had failed, Parnell did not lose standing with his supporters. Indeed, when he returned from his trip at the end of 1876, he picked up where he had left off: obstructing the workings of the House of Commons as much as he could. As he became more disruptive, he alienated Butt and all but a handful of his fellow Home Rulers. However, many militants, including some Fenians, appreciated Parnell’s combative spirit. In a sign of his growing influence, Parnell succeeded Butt as the president of the Home Rule Confederation of Great Britain in the summer of 1877. Butt, however, would remain chairman of the Home Rule party until his death in 1879.

In 1877, 1878 and 1879, poor harvests left many Irish farmers in desperate straits, especially those in the West. Urged on by Michael Davitt, a Fenian and an agrarian activist, Parnell turned his attention to the farmers’ plight and de-emphasized Home Rule. In June 1879, Parnell gave a rousing address to farmers in County Mayo, directing them to “keep a firm grip on their homesteads.” Farmers were only to pay the rents that they considered fair, not the amounts that the landlords were demanding. In October 1879, Davitt established the National Land League and installed Parnell as its president. Parnell then traveled around Ireland, delivering fiery speeches at mass meetings organized by the League.

In January 1880 Parnell set off again for America, seeking funds for the Land League and relief for the suffering farmers. He also wanted to connect with Irish American revolutionaries such as John Devoy who were backing the land agitation and the Home Rule movement. When he had visited three years earlier, Parnell was an obscure Irish politician who had little influence with American government officials. This time he was in a very different position. After arriving in New York City, Parnell spoke before a boisterous crowd of 7000 supporters. He then set off on a sixty city tour which would take him across the northeast and Midwest states and even into Canada.

From New York, he went south to Philadelphia and then headed north to Boston and to Lowell, Massachusetts. By mid-January, he was in Providence, speaking before at least 2000 supporters at the city’s Music Hall. Almost every day, he was off to a new city. In late January he was in the Midwest and by early February he reached Washington, D.C., where he was treated with great deference and invited to speak to the House of Representatives about the famine afflicting Ireland.

He then continued his whirlwind travels, heading as far west as Minnesota. In some states, Parnell was invited to address the legislatures, and in several cities parades were staged in his honor. By March, he was in Canada accompanied by Tim Healy, a young Home Ruler who hailed Parnell as “Ireland’s uncrowned king,” a nickname that would stick in the years following. While in Canada, Parnell learned that Parliament had been dissolved and that a general election would soon be held. Consequently, he had to cut his travels short. Still, the trip had been a remarkable success. He had criss-crossed much of the United States and had raised at least $350,000 for famine relief and for the Land League.

At some point during this trip, Parnell may have visited with Abby Woods Abbott. In the spring of 1880, she was expecting her fourth child, Caroline, who would be born in April. It is not clear where Abby was living at this time. The letters that Sam wrote in 1875 indicate that Abby was sometimes in Providence or Newport with her parents and sometimes in Boston with him where he was operating a thriving legal practice. Sam became even busier in 1879 when he was appointed a trustee of the Boston Public Library.

If Abby were at her parents’ home in Providence, she would have been just a short walk from the Narragansett Hotel where Parnell was staying. Parnell would no doubt have remembered the Woods’ house, having visited it in 1871. On the other hand, he may have seen Abby in Boston. The Abbotts had a home in Back Bay and Parnell was staying on Beacon Street at the home of his great-aunt, Euphimia Tudor.

“Charley’s Old Sweetheart”

While it’s not clear whether Charles had any contact with Abby in 1880, two other Parnells certainly did see her then. In the summer of 1880, John Parnell and his youngest sister Theodosia visited Newport and “heard that Miss Woods, who had in the meantime married a rich American, was living at a villa just outside the town.” Theodosia, who had met Abby in Paris ten years earlier, “said to me: ‘Come and let us call on Charley’s old sweetheart.’”

When they arrived at the Woods’ summer cottage,

she was in and welcomed us in the drawing room. She was still very pretty, charmingly

dressed, and vivacious in manner. She talked rapidly, evidently rendered somewhat nervous by the memories which we aroused. Suddenly she said: ‘Do tell me how is your

great brother Charles. How famous he has become! She stopped for a moment, and

seemed almost bursting into tears, then suddenly cried, as if from the bottom of her heart:

‘Oh, why did I not marry him? How happy we should have been together!’If Abby had seen Parnell earlier that year, she presumably would have said so. These

statements to John and Theodosia suggest that she had not seen him for a number of years.

Parnell and Mrs. O’Shea

When Parnell returned to Ireland, he campaigned tirelessly for Home Rulers, helping to expand their ranks in Parliament. In May the Home Rulers elected him chairman of the party. In July, one of the newly-elected members, Captain William O’Shea, and his wife Katharine, decided to invite Parnell to dinner to get to know him better. At this first meeting, Parnell fell passionately in love with Katharine much as he had with Abby ten years earlier. From this point on, he was constantly in touch with her and seeking opportunities to see her again. In October, he stayed with her while Willie was away, the first of many such visits. Parnell also started missing meetings at which he was scheduled to appear, leaving it to his aides to explain that the press of work had forced him to be absent.

By July 1881, Captain O’Shea had learned of the affair and challenged Parnell to a duel. While Katharine was able to prevent this from taking place, Captain O’Shea would remain a threat to them in the years following. O’Shea kept silent as Katharine gave birth to Parnell’s three daughters in quick succession: Sophie Claude, who was named for Parnell’s deceased sister Sophie, in February 1882; Clare in March 1883; and Katharine in November 1884.

The complications in his personal life notwithstanding, Parnell continued to triumph politically. In 1881 Gladstone passed a Land Act which provided many of the measures that the Land League had called for. Parnell criticized Gladstone for it anyway so as not to alienate his more militant supporters. Infuriated by his behavior, Gladstone ordered Parnell to be arrested and held in Dublin’s Kilmainham Jail. Being jailed by the English prime minister only added to Parnell’s popularity among the Irish. Recognizing his mistake, Gladstone soon began negotiating with Parnell. By April 1882, both parties agreed to the Kilmainham Treaty: Gladstone would release Parnell and provide additional assistance to the Irish farmers and Parnell would call off the Land League’s agitation. Parnell arrived back at the O’Sheas’ home just before his two-month old daughter, Sophie Claude, died.

In the years following, Parnell’s influence in Ireland and Irish America continued to grow. In June 1885 Parnell, frustrated with the slow pace of reform under the Liberals, sided with the Conservatives and brought down Gladstone’s administration. When elections were held that November, Parnell urged his supporters to back the Conservatives instead of their traditional Liberal allies. Winning eighty-six seats, the Home Rulers were able to return the Conservatives to power. Shortly after the election, however, Gladstone announced that he would support Home Rule for Ireland. In response, Parnell withdrew his party’s support for the Conservatives and shifted it to the Liberals, enabling Gladstone to return as prime minister in February 1886. True to his word, Gladstone made Home Rule his first priority. Although the bill failed in the House of Commons by a narrow margin due to defections among the Liberals, Parnell’s support among the Irish people did not fall. No Irish politician before him had ever been able to bring so much pressure to bear on the British Parliament.

Still, in the background was always the problem of Willie O’Shea. The Captain had held a seat in the House of Commons representing County Clare from 1880-1885. While sympathetic to the Home Rulers, he had never officially joined their party. In the 1885 elections he had failed to win a seat and when another became vacant in County Galway in 1886, he told Parnell he wanted it. To placate Willie, Parnell supported his candidacy and campaigned for him even though he was not a pledged member of the Home Rule party. When key Home Rulers objected, Parnell threatened to resign the leadership of the party. In the end, Parnell prevailed and O’Shea won the Galway seat, but the effort had been costly. Many of the Home Rule representatives resented Parnell’s actions and were suspicious about his motives.

While O’Shea was assuaged for the time being, three years later he decided to go public. In the spring of 1889, Katharine’s wealthy aunt had died and left her large estate to Katharine, but Katharine’s relatives successfully contested the will. With his hopes for an inheritance dashed, Willie sued Katharine for divorce, citing her adulterous relationship with Parnell. The divorce trial would destroy Parnell’s standing with the Irish people, undo the alliance he had forged with Gladstone and the English Liberals and bitterly divide the Home Rule Party into Parnellites and anti-Parnellites. In June 1891, Parnell was at last able to marry Katharine. Three months later, an exhausted Parnell contracted rheumatic fever and died a few days later in Katharine’s home, aged 45.

The Abbotts

In some respects, Sam and Abby Abbott’s situation in the 1880s paralleled that of Parnell and Katharine O’Shea. On the one hand, Sam became increasingly influential in Boston. From 1887-1889 he was the city’s Police Commissioner. His real passion, however, was the Boston Public Library. As a trustee and eventual president of the library, Sam was a driving force behind the decision to erect a new building on Copley Square and entrusted its design to his friend Charles McKim of the firm of McKim, Mead and White. Sam also commissioned John Singer Sargent, James McNeill Whistler and other distinguished artists to decorate the library’s interior. At the same time, Sam and Abby’s relationship seems to have deteriorated. Maryalice Huggins, an independent scholar who has studied the Woods family and has interviewed several of her relatives, believes that the marriage had broken down by 1880. She says that with Abby often visiting her parents, Sam “began to roam and fell in love with another woman.”

While Huggins does not prove her contention, there are reasons why it is plausible. Sam’s 1875 letters indicate that the marriage was then under stress with Abby often ill or anxious. In the 1880s Sam traveled extensively in Europe with Charles McKim, looking for inspiration for the new library. It does not appear that Abby accompanied Sam on these trips. When Abby died in 1895—like Parnell, only living to be 45—she was in Providence, not Boston. She was buried in Providence at Swan Point Cemetery. In the year following Abby’s death, Sam married Maria Dexter and moved with her to Rome, where he became director of the newly-established American Academy of Rome. After Sam remarried, three of his four daughters broke off contact with him.

Conclusions

While Abby appears to have regretted her decision to reject Parnell, her relatives remained hostile to him in the years following. In 1905 a member of the Woods family went to the trouble of excising all references to Parnell in the letters that Abby sent to her mother. In the 1920s, Abby’s brother John Carter Brown Woods wrote to Abby’s daughter, Helen Washburn, who was then in Rome. As St. Patrick’s Day had just passed, Woods offered his thoughts on the Irish. After dismissing them as a “treacherous, unreliable race,” he turned to Parnell: “The first, and only great Irishman I ever knew was Charles Stuart[sic] Parnell, who wanted to marry your mother. He ran true to his people’s form and proved to be a bad lot, although he laid the beginnings of Ireland’s independence.”

Although John Woods shuddered to recall that his sister had almost married Parnell, historians will find their relationship much more intriguing. If they had been married in the 1870s, then Parnell would have been able to devote his full energies and peerless political skills to Home Rule without the serious hindrances that he faced. Abby would have moved with him to Ireland and might have helped to bankroll his campaign. Instead of fracturing over the O’Shea divorce, Parnell and his allies might have gained Home Rule in the 1880s or ’90s. Yet, even if Home Rule remained out of reach because of British opposition, constitutional nationalists would have been dominant in Irish politics while revolutionaries such as the Fenians and their successors, the Irish Republican Army, would likely have been at the margins.

1 R.F. Foster, Charles Stewart Parnell: The Man and his Family (Atlantic Highlands, NJ, 1976), 75-77.

2 For the Fenian rising, see R.V. Comerford, The Fenians in Context: Irish Politics and Society, 1848-82 (New

York, 1985).

3 F.S.L. Lyons, Charles Stewart Parnell (Suffolk, 1978), 32-35; Robert Kee, The Laurel and the Ivy: The Story of

Charles Stewart Parnell and Irish Nationalism (London, 1993), 37-44.

4 Maryalice Huggins, Aesop’s Mirror: A Love Story (New York, 2009), 163. David McCullough estimates that there

were about 4500 Americans in Paris in 1870. See his The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris, 1830-1900 (New

York, 2011), 264.

5 See Charles Rappleye, Sons of Providence: The Brown Brothers, the Slave Trade and the American Revolution

(New York, 2006); William G. McLoughlin refers to John Brown as a “merchant buccaneer” in his Rhode Island: A

History (New York, 1986), 180.

6 The prior treasurers were all members of the Brown family: John Brown, Nicholas Brown, Moses Brown Ives, and

Robert Hale Ives. See Reuben Guild, History of Brown University (Providence, 1867), 335-336.

7 For the Paris Exposition, see McCullough, 219-220.

8 John Howard Parnell, Charles Stewart Parnell: a memoir (New York, 1914), 74.

9 Ibid., 75.

10 Abigail Woods to Anne Brown Francis Woods, February 10, 1870, Alva Woods Family Papers, Folder 20, Box

12, Rhode Island Historical Society, Providence, Rhode Island [hereafter abbreviated AWFPRIHS].

11 Abigail Woods to Anne Brown Francis Woods, May 27, 1870, Folder 22, Box 12, AWFPRIHS.

12 Abigail Woods to Anne Brown Francis Woods, June 26, 1870, Folder 22, Box 12, AWFPRIHS.

13 Abigail Woods to Anne Brown Francis Woods, June 3, 1870, AWFPRIHS. John M. Read, Jr. was appointed

American consul to France by President Grant in 1869 and minister to Greece in 1873. See National Cyclopedia of

American Biography 11 vols. (New York, 1892), 2:223-224.

14 Abigail Woods to Anne Brown Francis Woods, June 29, 1870, Folder 22, Box 12, AWFPRIHS.

15Abigail Woods to Anne Brown Francis Woods, June 30 and July 3, 1870, Folders 22 and 23, Box 12, AWFPRIHS.

16 Abigail Woods to Anne Brown Francis Woods, August 7, 1870, Folder 23, Box 12, AWFPRIHS.

17 See Geoffrey Wawro, The Franco-Prussian War: The German Conquest of France, 1870-1871 (New York,

2003).

18 Abigail Woods to Anne Brown Francis Woods, September 4, 1870, Folder 24, Box 12, AWFPRIHS.

19 Abby Woods’ letters were typed up, probably in 1905, and all references to Parnell were excised. For three of the letters, the typist inadvertently put the year as “1905” instead of “1870.” See Folder 22, Box 12, AWFPRIHS.

Maryalice Huggins attributes the deletions to “Victorian shame….The Woodses did not want their daughter’s name

associated with Parnell after he was accused of adultery in the scandalous divorce proceedings covered in the press.” Huggins, 262.

20 Abigail Woods to Anne Brown Francis Woods, September 15, 1870, Folder 24, Box 12, AWFPRIHS.

21 Abigail Woods to Anne Brown Francis Woods, September 25, 1870, Folder 24, Box 12, AWFPRIHS.

22 Anne Brown Francis Woods to Marshall Woods, September 26, 1870, Folder 8, Box 12, AWFPRIHS.

23 Anne Brown Francis Woods to Marshall Woods, September 29, 1870, Folder 8, Box 12, AWFPRIHS.

24 Abigail Woods to Anne Brown Francis Woods, September 27, 1870, Folder 24, Box 12, AWFPRIHS.

25 Abigail Woods to Anne Brown Francis Woods, October 10, 1870, Folder 24, Box 12, AWFPRIHS.

26 Marshall Woods’ father, Dr. Alva Woods (d. 1887) was a Baptist minister who briefly served as president of

Brown University in the 1820s.

27 In fact, Alva Woods, much like Anne Woods, was ambivalent about the relationship. See Alva Woods to

Marshall Woods, August 13, 1870, Folder 8, Box 12, AWFPRIHS.

28 Abigail Woods to Anne Brown Francis Woods, October 9 and 16, 1870, Folder 24, Box 12, AWFPRIHS.

29 J. Parnell, 77. John Parnell reported that Charley went to Paris after he received Abby’s letter in hopes of seeing her before she set sail. However, Abby had left Paris in August because of the war and had not returned.

30 Huggins, 185, 263. The telegram was in the Abbott Family Papers in the Rhode Island Historical Society but was

de-accessioned in 2010.

31 A brick Italian Renaissance villa designed by Richard Upjohn, the Woods’ home was the largest in Providence

when it was completed in 1863. Now known as the Woods-Gerry House, the property was acquired by the Rhode

Island School of Design in 1959 and houses the school’s Admissions Department and student art galleries. See

William McKenzie Woodward, PPS/AIAri Guide to Providence Architecture (Providence, RI, 2003), 239-240; Ada

Louise Huxtable, “Architecture: This is Silver Lining Day,” New York Times, January 25, 1970; Huggins, 199-203.

32 J. Parnell, 78.

33 Foster, 110.

34 J. Parnell, 78-79.

35 Ibid., 78-80; Foster, 110-111; Lyons, 38-39.

36 Popularly known as “Grattan’s Parliament,” the body had considerable authority from its establishment in 1782

until its dissolution in 1800. While Sir Henry Grattan was the dominant figure, Sir John Parnell (d. 1801) played an important role as well, serving as Chancellor of the Exchequer in the 1780s. See R.B. McDowell, Grattan: A Life (Dublin, 2001).

37 Kee, 55-57.

38 John Parnell returned to politics later in life, serving as a Home Rule MP from 1900-1905. See Kee, 612.

39 Ibid., 58-62.

40 The seat had been held by John Martin (1812-1875), a prominent Protestant nationalist from Ulster who had taken

part in the 1848 Young Ireland rising and had been jailed in Australia. In 1871 he had been elected to the House of Commons for County Meath. See Richard Davis, The Young Ireland Movement (Dublin, 1987).

41 Kee, 105-106.

42 Delia Parnell had inherited her father’s estate in Bordentown, New Jersey upon his death in 1869. Fanny (1848-

1882) co-founded the Ladies Land League with her sister Anna in 1880. See Jane M. Cote, Fanny and Anna

Parnell: Ireland’s Patriot Sisters (New York, 1991).

43 For the Centennial Exhibition, see Dee Brown, The Year of the Century: 1876 (New York, 1966), 133-137.

44 Lyons, 56.

45 See Culver Sniffen to Charles Stewart Parnell and John Power O’Connor, October 17, 1876, printed in The

Papers of Ulysses S. Grant 31 vols. (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005) ed. John Y. Simon

27: 336n.

46 Ibid., 337n.

47 Kee, 125.

48 Josiah Gardiner Abbott was a Boston lawyer who would be elected to Congress as a Democrat in 1876. See

Biographical Directory of the American Congress, 1774-1996 (Alexandria, VA, 1997), 551.

49 See for example, Samuel Abbott to Josiah Gardiner Abbott, April 9, 1875, Josiah Gardiner Abbott Papers,

Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston Massachusetts [hereafter abbreviated JGAMHS].

50 Samuel Abbott to Josiah Gardiner Abbott, June 24, 1875, JGAMHS.

51 Genealogies of Rhode Island Families 2 vols. (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1983), I: 186. Abby’s

health was still very uncertain in 1877. Sam’s mother wrote to her husband Josiah Gardiner Abbott who was again

visiting Europe: “Abby is not at well. She has lost 10 pounds in the last month and that worries Sam.” Caroline

Abbott to Josiah Gardiner Abbott, July 31, 1877, JGAMHS.

52 For Davitt, see T. W. Moody, Davitt and Irish Revolution, 1846-1882 (New York, 1981).

53 Devoy, Davitt and Parnell had brokered an agreement in 1879 known as the “New Departure.” Fenian leaders in

Ireland rejected the agreement and remained solely focused on gaining independence for Ireland through means of

force. For the “New Departure,” see Thomas N. Brown, Irish American Nationalism (New York, 1966), 85-98.

54 “Parnell’s Noisy Hearers: Seven Thousand Persons Greet the Irish Member,” New York Times, January 5, 1880.

55 Providence Daily Journal, January 19, 1880. The Music Hall, located on Westminster Street in downtown

Providence, had a capacity of 2200. It was damaged in a fire in 1905 and replaced by another structure. See John

Hutchins Cady, The Civic and Architectural Development of Providence (Providence, 1957), 160.

56 He addressed the legislatures of both Virginia and Iowa. See Kee, 220, 223.

57 Kee, 223.

58 Ibid.; Lyons, 108.

59 Katharine O’Shea Parnell claimed in her memoir that Parnell had visited with Abby Woods Abbott during his

1880 tour. However, she wrote her account in 1914 and may have gotten her dates confused. See Katharine Parnell,

Charles Stewart Parnell 2 vols. (London, 1914) 1:138-139.

60 Abby had given birth to a third daughter, Anne, in September 1878. See Genealogies of Rhode Island Families, I: 186.

61 Huggins, 188; Walter Muir Whitehill, Boston Public Library: A Centennial History (Cambridge, MA, 1956), 140.

62 Providence Daily Journal, January 17, 1880.

63 The Boston Directory (Boston, 1879), 50; Boston Pilot, January 3, 10, 17, 1880. Parnell’s mother’s full name was Delia Tudor Stewart. Euphimia was the widow of Delia’s uncle Frederic Tudor. See Foster, 55-58.

64 Thedosia Parnell (1853-1920) married Claud Paget, an English naval officer in 1880, a few weeks after her visit with Abby Woods Abbott.

65 J. Parnell, 80-81.

66 Kee, 295-296.

67 Ibid., 420-427.

68 Ibid., 475-492.

69 For the difficulties Parnell faced because of the Liberal alliance, see Patrick O’Farrell, Ireland’s England Problem (New York, 1971), 179-188.

70 Lyons, 220-233.

71 See Frank Callanan, The Parnell Split, 1890-1891 (Syracuse, NY, 1992).

72 “S.A.B. Abbott Is Dead in Rome,” New York Herald Tribune, June 20, 1931.

73 Whitehill, 148-162.

74 Huggins, 189.

75 Whitehill, 149, 158.

76 Abby died of chronic intestinal nephritis. See Swan Point Cemetery Records, RIHS.

77 See Mildred ? to Helen Abbott Washburn, September 23, 1931, Washburn Family Papers, RIHS [hereafter

abbreviated WFP]. Writing from Rome shortly after Sam’s death, this family friend told Helen, “I think all the

troubles arose when he married Maria.”

78 See footnote 19.

79 John Carter Brown Woods to Helen Abbott Washburn, March 18, 1927, WFPRIHS.

80 For scenarios of this sort, see Alvin Jackson, “British Ireland: What if Home Rule had been enacted in 1912?” in Niall Ferguson, ed., Virtual History: Alternatives and Counterfactuals (New York, 1999), 175-227; Alan J. Ward,

The Easter Rising: Revolution and Irish Nationalism (Wheeling, IL, 2003), 41-54.

This article a fully footnoted version of the article that appeared inVolume 23 No.1 (Jan/Feb 2015). The article as originally published can be viewed on the digital version of the magazine at: https://staging.historyireland.com/digital-edition/