By Cian Manning

On 14 February 1875 the wealthy couple Francis and Mary Shortis, of 31 The Mall, Waterford, became the parents of Francis Valentine Cuthbert Shortis, known as Valentine to distinguish him from his father. The elder Shortis was a native of Clonmel and had become a prominent figure in Waterford city as a cattle dealer. Francis Shortis was one of the founder members of the Irish Cattle Traders and Stockowners’ Association. His wife was the daughter of Captain Thomas Hayes, an old-time mariner when trade between the south-east of Ireland and North America was at its height. Mary Shortis was a productive figure in her local community, associated with charities such as the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (of which she was the first secretary), St Joseph’s Clothing Society, the Indoor and Outdoor Maternity Society and the Waterford Jubilee Nursing Association. They were a very well-respected couple in Waterford society who could call on neighbours and friends from photographers to politicians and solicitors. One would think that their son, with such a well-off start to life, would have followed a similar path, but Valentine was to become an infamous figure in Canadian legal history.

Animal abuse and bad behaviour

Young Valentine was an only child who displayed rather unsettling behaviour quite early on in his childhood and schooling, which led to his being nicknamed ‘cracked Shortis’. A classmate, John Ryan, described Valentine as a ‘hot-tempered fool’ who seemed unable to control his behaviour and frequently complained of headaches. It was later noted that both sides of his family had a history of mental illness. Shortis had been cruel to animals on a number of occasions—from stabbing his father’s dog to shooting a cat several times to see how many bullets it could take. A fascination with firearms bordering on obsession saw him firing at the portholes of passing ships and using Waterford’s iconic clock tower as target practice. The most unsettling incident from his years in Ireland was his attempt to trample a child with his pony. His father felt that these behaviours were down to his overbearing mother and that the best thing for him would be to strike out and make his own way in the world.

In 1893, aged eighteen, Valentine Shortis boarded the SS Laurentian to Canada and settled in Montreal. There for nearly a year he only obtained work when his mother visited him for a month. He became private secretary to Louis Simpson, the general manager of the Montreal Cotton Company, Valleyfield, Quebec. It seemed as if both his professional and his personal life were going well when he started a relationship with Millie Anderson, the daughter of the owner of the rival Anderson Foundry. Owing to his fraternisation with the cotton mill’s rivals, his poor work ethic and his low rate of productivity, his contract was not extended beyond his year of service. When denied a reference by Simpson, Shortis is believed to have proclaimed: ‘Every dog has its day; it will be my turn next’. He survived on hand-outs from his parents in Ireland, but in January 1895 his mother wrote him a deliberately misleading letter, claiming that the family fortune was lost and that Valentine must now fend for himself. At the time he was contemplating a new life with Millie Anderson out West, but, rather than inspiring him to take a positive direction, events would spiral out of control.

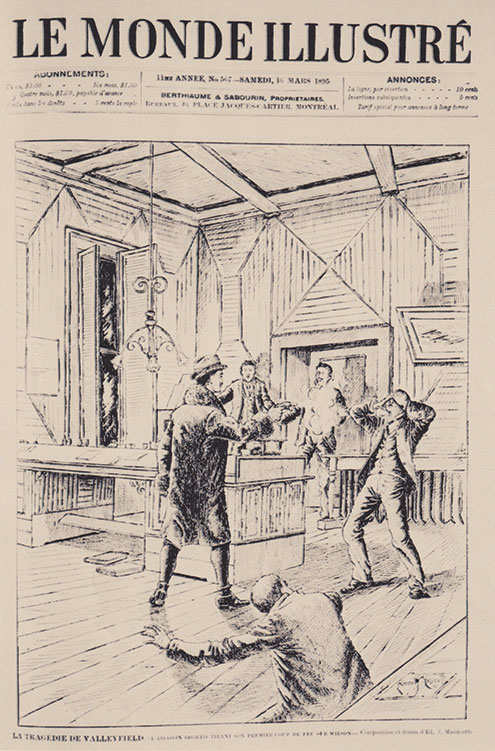

The robbery

In order to fund his future with Anderson, Shortis planned to rob the pay office of his previous employers at the Valleyfield cotton mill. Leaving Millie after 10pm on 1 March 1895, he arrived at the offices of the mill and was cordially chatting to his former colleagues as they set out the pay-packets to be distributed to workers the following day. It was estimated that between $12,000 and $15,000 was in envelopes before him. As they were being placed in the safe, Shortis removed a loaded company gun from a desk drawer and opened fire. He fatally shot John Loy, a clerk whose father was the mayor of Valleyfield, and the watchman, Maxime Leboeuf. Another clerk, Hugh Wilson, was wounded but managed to escape to get help. John Lowe, the paymaster at the mill, acted quickly by grabbing the funds and locking himself in the vault. In one last attempt to get his hands on the mill’s money, Shortis set the building on fire in an attempt to smoke Lowe out of the vault. When authorities arrived at the scene, Shortis gave himself up and was found to have a loaded .22 calibre revolver on his person. He was charged with the murder of the two men.

The trial

The trial before Judge Michel Mathieu was originally set for Beauharnais but was switched to Montreal when a mob attempted to lynch Shortis. It began on 1 October 1895 with the Crown prosecutor, Donald Macmaster, seeking a conviction for murder. Macmaster was unable to find any evidence that Shortis was ever arrested or detained in a mental asylum in Waterford or anywhere in Ireland. His character was eccentric rather than insane and he had to account for his actions. Three months before the murders, Shortis had shot at two mill workers ‘western-style’ with two revolvers for ‘talking too loudly’. The prosecution doubted the testimonies provided by the defence and argued that Shortis was clearly in possession of his faculties if his parents had sent him to Canada in the first place. They objected to the defence’s plea of insanity on the grounds that it went beyond the stipulations of the criminal code of Canada, as there were no provisions for him to be confined in an asylum if proven insane. This argument was dismissed by the judge. The prosecution concluded that the robbery was premeditated and that Shortis should be found guilty.

His defence was led by J.N. Greenshields, who sought to convince the jury that the defendant was insane. His opening plea was that Shortis had been

‘… labouring under natural imbecility and disease of the mind to such an extent that rendered him incapable of appreciating the nature and quality of the act of knowing such an act was wrong; and was at the time suffering from unconscious and disease of the mind by which a predetermination of his will was excluded; that he was in a state of madness and was insane.’

Both prosecution and defence went to Waterford before the trial to obtain witness testimonies and documentary evidence of Shortis’s character. They would gather the written statements of 48 people, with two heard in person at the trial. One was his former schoolmate John Ryan, while the other was Robert Dobbin, his father’s solicitor in Waterford. A statement from Richard Malone, who worked in the Shortis cattle business, outlined how Valentine had stuck a pitchfork into a cow and appeared to enjoy torturing animals. Other incidences of unsettling behaviour, combined with records of a history of mental illness in the family, gave the defence, in their opinion, ‘sufficient evidence to convince a jury that he [Valentine] is beyond a doubt insane’. In addition, the defence used the examinations of Shortis by four experts on mental illness to conclude that he was insane when he shot his victims.

After 29 days (at the time the longest trial in Canadian history), on 3 November the jury returned a verdict of guilty and Shortis was sentenced to be hanged on 3 January 1896.

Campaign for commutation

Throughout the trial Valentine Shortis’s parents were present in court in Quebec. It was believed that it had cost the family £10,000 to fight the case. After the sentence, Francis Shortis returned to Ireland to gather petitions, as they sought ‘royal clemency’ from the governor-general of Canada, who had the power to commute the sentence after discussion with the federal cabinet.

A meeting of Waterford Corporation adopted a petition for the commutation of Valentine’s sentence on the grounds of insanity. The Corporation believed that there was enough evidence to support this, with the testimony of over twenty witnesses at a special convention held by an American judge in Waterford. By the end of November, public bodies in Waterford, Cashel, Tipperary and Clonmel Corporation adopted petitions and memorials in support of Val Shortis.

Mary Shortis pleaded with Prime Minister Mackenzie Bowell, Justice Minister Charles Hibbert Tupper, and even with the wife of the governor-general, Lady Aberdeen, to influence her husband to intervene on the matter of her son’s death sentence. All concerned received a deluge of letters seeking the commutation of Shortis’s sentence. Tensions between Catholic Quebec and Protestant Ontario were heightened on the issue of the hanging of Quebecois Amedée Chatelle in Ontario. Chatelle had pleaded insanity but did not have his sentence commuted. What had appeared to be the tragic crimes of a troubled young man now took on a role in public discussion of numerous issues that concerned Canadian society: the colonial experience, the differences between the English- and French-speaking communities, and religion.

Rumours abounded about the wealth and rank of the Shortis family in ‘British’ society—that Francis Shortis was the illegitimate son of Prince Albert, that Mary was a close friend of Lord and Lady Aberdeen—though all these allegations were unsubstantiated. Furthermore, the division in Canadian society on the matter was mirrored at cabinet level, where there was deadlock on how to deal with Shortis. They eventually decided to let Lord Aberdeen resolve the issue. On 31 December 1895, the governor-general commuted Shortis’s death sentence to life imprisonment, initially in St Vincent de Paul Penitentiary, Montreal.

‘Known to hundreds, but only a few had any inkling of his past’

Valentine Shortis spent the next 42 years in either asylums or prisons. In 1937 he was found to be mentally competent and was paroled on 3 April. He moved to Toronto, where he lived under an assumed name and where he died of a heart attack in 1941. The Telegram noted that he ‘was a familiar figure in Toronto … Distinguished by his goatee, monocle and cane, he was known to hundreds, but only a few had any inkling of his past.’ His mother had died in 1907. His father remarried and later died at Tramore in 1932, having amassed personal estates in England and Ireland to the value of £46,805 15s 4d. Under the will there was a conditional annuity of £200 to Valentine. For the last few years of his life he no longer had to worry about money.

Cian Manning is an independent researcher from Waterford.

FURTHER READING

E. Butts, ‘Valentine Shortis case’, in The Canadian Encyclopaedia (Edmonton, 2013).

M.L. Friedland, The case of Valentine Shortis: a true story of crime and politics in Canada (Toronto, 1988).